An ode to my late, bookish dad.

Great readers aren’t born, they’re made. As an adoptee, I often wonder if I would’ve become a writer if I’d been raised by other parents. But before I was a writer, I was a reader, encouraged by both my parents. Here, I would like to eulogize in books my father, Ralph Stephens, who died in November at the age of 89.

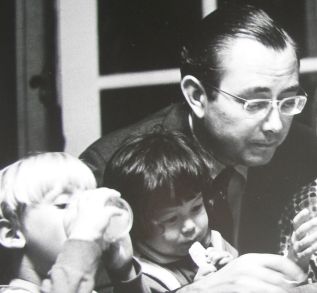

I grew up in a house full of books, where reading was revered. My parents read to my siblings and me every night. I have cozy memories of being safely ensconced in my father’s lap, or snuggling in bed with my mother, as they read Stuart Little, The Wind in the Willows, Charlotte’s Web, Pippi Longstocking, and other childhood classics to me.

While my mother was the fiction reader, my father was the scholar. He didn’t dally with fanciful stories and made-up characters. He was interested in the forces that shaped the world we now inhabit and read widely on politics, international relations, government policy, anthropology, and history.

In a perfect world, my father would’ve been a professor of early Christian history instead of an economist. A staunch atheist, he was fascinated by the origins of Christianity, which he saw as the fundament of the contemporary Western world. His bedside table was stacked with titles such as The History of the Church by Eusebius, The Writings of St. Paul, and Paul Barnett’s Jesus & the Rise of Early Christianity: A History of New Testament Times.

Early Christianity arose during Roman times, and he consumed many shelves of books on that era. And much of Roman culture was influenced by Ancient Greece, which produced the first literary works of Western civilization. Thus, my father was well versed in the biographies of its important political figures and the works of its major thinkers and storytellers, too.

It wasn’t just history, though. My father would study up on everything that interested him. His passion was fly fishing, and he acquired heavy tomes on the lifecycles of bugs that trout eat, the ecology of the great fly-fishing rivers of the world, and the biology and behavior of trout.

He wasn’t interested in how-to or technique manuals; he wanted to understand the intellectual aspects of the sport, which he saw as a way of communing with nature. One year, he sent his children a list of books that we might gift him for his birthday. They all had to do with fly fishing. I gave him Nymphs: The Mayflies, the Major Species by Ernest G. Schwiebert.

For work and for pleasure, my father traveled the world, and he always did his background research first. His preferred guidebooks were the Blue Guides; the more history and the less shopping and dining, the better. He had a grasp on the basics of the history, modern governance, economy, and geography of a place before he ever stepped foot in it.

For most of his life, the only fiction my father read was Shakespeare. He and my mother were subscribers to the Shakespeare Theatre Company, and he perused each play before seeing it performed, often also seeking out supplementary texts to further illuminate and enhance his theater-going experience. A habitual note-taker, he jotted down important ideas and details on index cards that he would take to the performance tucked into the front pocket of his button-up shirt for handy reference.

In the ninth and final decade of his life, my father became a convert to the novel. Though not a zealot by any means, he came to appreciate it as an artform with unique powers to frame and philosophize on the human condition, to transport readers to distant historical times and places, and as snapshots of the intellectual past.

For 15 years, he hosted a book club based on the literature humanities texts from the core curriculum of his alma mater, Columbia University. They started with the Greeks and slowly and carefully made their way through the history of Western civilization, until finally, they arrived at the novel.

The first novel I discussed with him was The Princess of Cleves, and while he wasn’t wowed, neither was he repulsed. He could see that fiction had its place in history-telling. His enthusiasm grew with later works, such as The Brothers Karamazov and Middlemarch, which he talked about in great detail.

In my experience, most people have their minds rigidly molded by early adulthood and cling to their thought patterns until death. My father’s ability to embrace an artform he had long rejected, and to discuss the strengths of the novel with an open mind, is testament to the man I admired so much. His mind was never a closed door, and he reserved the right to change course after reasoned consideration.

(After decades of donating generously to Columbia, he cut them off when they suppressed the rights of students and faculty to protest over Gaza, donating the money instead to pro-Palestinian and human-rights organizations.)

His final book was Jane Eyre. Though he never read my novel, I like to think that after the book club tackled works like The Metamorphosis and Song of Solomon, he would’ve worked his way up to it.

I miss my father terribly, and my world will never be the same without him. But he’s with me every time I open up a book. Every day, I carry on his legacy.

Alice Stephens is the author of the novel Famous Adopted People.