Conjuring the internal geography of imagined lands.

Faulkner had his Yoknapatawpha County and Anderson his Winesburg. Rion Amilcar Scott’s Cross River, Maryland, had houses, slapboxing cultists, and even, once-upon-a-time, God. The writer’s adage, “Write what you know,” gets thrown around, and while some authors set their stories in a specific borough or beach town, others, like me, tend to bend facts and distort geographies of imagined lands.

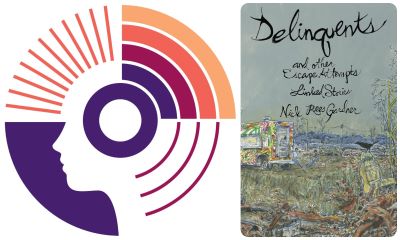

One reason to fictionalize a town is to maintain distance, which, I have to admit, was on my mind when I drafted the map of my own Westinghouse, Ohio, for Delinquents and Other Escape Attempts. But there’s more to this elaboration. Scott imbues his most recent collection, The World Doesn’t Require You, with a mythology of Cross River. As Barry Lopez puts it in his essay “Landscape and Narrative,” a place isn’t only iconic views and architecture but “its geology, the record of its climate and evolution.” When setting a series of stories in a fictional locale, you have the option to show how people and place have affected each other over time.

As I write this, I am leaning into my fourth year in Washington, DC. Before this was Ohio, and before that, a two-year stint in a Louisiana commune. Right out of high school, I lived for six months in Olympia, Washington. If you pause long enough, look deep enough, you can see how the external landscapes mentioned by Lopez change who we are, who our characters are.

While in Ohio, I hid in the basement bathtub with the radio tuned to the tornado watch; in Louisiana, I boarded up windows in hurricane winds so strong, they ripped cigarettes from my mouth. Compare shoveling your car out of a two-foot snowdrift in Ohio to the three inches of powder that shuts down Olympia or DC.

My first couple years in DC were solitary. I walked Rock Creek Park daily, wandered through the Brutalist architecture and tourists, cyclists and dog-walkers. I was able to find enough lived distance from my Ohio hometown to write my fictional Westinghouse, with its junkyards, abandoned buildings, and DIY art houses, as it was meant to be: a place unobscured by my experiential fingerprints.

I was also able to remember my hometown slightly askew and without feeling the need to stick to geographical facts; I was better able to merge my wholly Ohio stories with anecdotes from other places and other people. As I talked with outsiders about their views of small Ohio towns, I was able to limn a place that defied outsider expectations and encouraged readers to see the Midwest in a new light.

A pervasive myth about DC is that most who live here aren’t really from here. But that raises questions about what being from a place really means. People roam all over, and their interactions with flora and fauna or architecture and art change who they are just as their interactions with that place — say, picking a bouquet of flowers, cutting down a tree, or sticking gum to a wall — change that place.

Though I still enjoy my solitary walks in DC, I’ve more recently found a wonderful literary community here. Some members are born-and-raised DMVers. A couple are from Ohio or lived there for a while. (DC is filled with ex-Ohioans: Beware!) While my story collection puts place — the region where I was born and raised — front and center, my time in DC, with all its customs and quirks and characters, has allowed me to recontextualize Westinghouse, Ohio, to see it and, I hope, show this region in a fresh light from a new, more universal angle.

[Editor’s note: This piece is in support of the Inner Loop’s “Author’s Corner,” a monthly campaign that spotlights a DC-area writer and their recently published work from a small to medium-sized publisher. The Inner Loop connects talented local authors to lit lovers in the community through live readings, author interviews, featured book sales at Potter’s House, and through Eat.Drink.Read., a collaboration with restaurant partners Pie Shop, Shaw’s Tavern, and Reveler’s Hour to promote the author through special events and menu and takeout inserts.]

Nick Rees Gardner works as a beer and wine monger, book reviewer, and writing teacher in Washington, DC. His writing and criticism have appeared in Adroit Journal, BarrelHouse, Epiphany, and many other journals. His books include So Marvelously Far (Crisis Chronicles Press, 2019), a collection of sonnets about addiction and recovery in the Rustbelt; Hurricane Trinity (Unsolicited Press, 2023), a climate-change novella; and a collection of linked stories, Delinquents and Other Escape Attempts (Madrona Books, 2024). He’s received support from the Elizabeth George Foundation, Vermont Studio Center, the De Groot Foundation, and the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities.