Witness Carrie Bennett’s jarring take on our coming cataclysm.

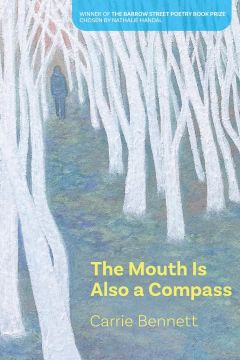

Bundle up before you open The Mouth Is Also a Compass (Barrow Street) by New England poet Carrie Bennett, and make sure you’re wearing sturdy shoes. This collection is an expedition through an icy — no, make that slushy — hellscape, a trek into a future we wish we could avoid.

It’s a vision of the ecopocalypse that looms like a ghostly glacier beyond the daily headlines. But Bennett is not resigned, nor is she content to simply sound the alarm. Rather, she seeks to map a way forward. “On any given trail there is a yearning,” she writes in the poem “How to Survive Common Diseases: Wolf Envy”:

Using a lightning road map will help

illuminate an opened mouth.

Indeed, the final third of her collection is formatted as a guidebook, “The Explorer’s Handbook of Survival.” The question is not, however, how we may survive ecocide but whether we merit survival. This is no indictment; Bennett believes we are worth saving, along with the rest of the planet.

The book is divided into three sections, each markedly different in presentation. The first, “To Break Open the Sea,” mixes prose and free verse to convey a linear narrative through richly evocative imagery. “I crave a sky the color of peaches,” Bennett writes in the poem “The Evidence Escaped like Smoke.” “I crave warm water with lemon.”

In “Every Field Contains a Frozen Bird,” she tells us of a meadow where “Maps scatter like soft stars” and “bright flags wave…a sky filled / with songbirds I will never see again.” Here is grief, yearning, and ache for what may be lost. “Will I forget / the red beak of a cardinal?”

In the second section, “Fragments Inside the Storm,” disjointed words and phrases sprawl across the pages, the lines surrounded by negative space. I was reminded of certain recent translations of the remnants of Sappho’s works, gleaned from strips of parchment wrapped around Egyptian mummies, tantalizing in their incompleteness. In Bennett’s book, it’s as if we’ve come across an arctic explorer’s log frozen in a melting snowbank, the moisture of the thaw blotting and smearing whole strings of words. The result is enigmatic, post-linear:

memory

is a reversehurricane

no entry couldsummon all

the dead

In the final section, readers will find a return to the lyrical disguised as a series of chapters from an imagined survival handbook. Seemingly prosaic titles such as “How to Survive Sub-zero Temperatures” and “How to Survive the Long Night” belie their sibylline contents and give way to the arcane — “How to Forget Snow,” “How to Dream of the Last Ice Age.” Here, in the poem “How to Greet the End,” the poet becomes oracle, speaking in riddled code:

When the wind makes the sound of a struggling star, knocks on the door of your throat. When the wind becomes a clock…At least there is a wolf to watch you weep.

“Even the stars will die eventually,” she then informs us in “How to Find the Last Ice Age.” Yet as fatalistic as these words may sound, a note of optimism can be heard in the poem “How the Last Ice Age Appears” in the closing pages:

A valley of green light rises from the water. The ocean continues to beat its enormous liquid heart.

Although it’s logical to view the collection’s sections as sequential, they can also be seen as parallel narratives — the same cataclysm explored from three perspectives. Either way, what we are witness to is ecocide, and Bennett brings this ongoing trauma to a personal level. Have we so lost touch with the wild from which our species arose that there can be no return? Or, as Bennett suggests, by reacquainting ourselves with our own inner wilding, will we remember the cardinal and the wolf, the fields of bright flowers and the snow?

Bennett raises these questions while leaving it up to readers to discover the answers. This is what good poets do. It is not their job to deliver solutions but to blaze the trail. The journey is ours to choose. Buckle up.

W. Luther Jett is the author of Flying to America and six chapbooks of poetry.