On South Asian identity and the American Dream.

On the campaign trail, Kamala Harris used her mother’s “coconut tree” metaphor to make a political point, but I suspect the comment was more complex than Harris let on, perhaps even darker than she permitted herself to hear. Maybe that’s not surprising. Harris wouldn’t be the first politician to simplify human life for political purposes (nor the first woman to misinterpret her own mother).

In a viral clip, Harris says, “My mother used to — she would give us a hard time sometimes, and she would say to us, ‘I don’t know what’s wrong with you young people. You think you just fell out of a coconut tree?’” At this point, Harris laughs, then explains her mother’s message: “You exist in the context of all in which you live and what came before you.”

She goes on to talk about the importance of equity in education, noting that not all students are offered the same opportunities to succeed given disparities in financial resources and family backgrounds. “None of us lives in a silo,” Harris explains, and “everything is in context.” The point is, more or less, the same one that Barack Obama made in the 2012 presidential campaign when he said, “Somebody helped to create this unbelievable American system we have that allowed you to thrive. Somebody invested in roads and bridges. If you’ve got a business, you didn’t build that.”

Success and failure aren’t ours alone. Rather, many others — our families and ancestors, political systems, communities, fellow citizens and neighbors — help us stand on our own two feet, or not. None of us is an island.

Harris’ mother, Shyamala Gopalan, was the eldest of four children. She did well in college in Delhi and then, in 1958, at the age of 19, went alone to Berkeley, California, to pursue a graduate degree. The plan was to study and then return to India to marry. Her parents had an arranged marriage, and it was assumed Shyamala “would follow the same path,” Harris writes in her memoir, The Truths We Hold.

But life intervened. Shyamala fell in love with Berkeley and with her boyfriend, Donald Harris, during the height of the Civil Rights Movement. Kamala Harris calls her mother’s romance with her father “the ultimate acts of self-determination and love.” Defying her destiny (the marital arrangement waiting for her in India), Shyamala chose to make her own life, navigate her own path, in matters both public and private. How American.

The marriage wasn’t easy, though, and Shyamala and Donald soon split up. They were “so young,” writes Harris, and not yet “emotionally mature.” The years after the separation seemed to have been difficult, with Shyamala raising two girls alone, working, studying, and moving around for jobs. Harris is circumspect when writing about her parents’ marriage, but she allows herself to say that “it was hard on both of them” and that “divorce represented a kind of failure [Shyamala] had never considered.”

She adds that her mother’s “marriage was as much an act of rebellion as an act of love. Explaining it to her parents had been hard enough. Explaining the divorce, I imagine, was even harder. I doubt they ever said, ‘I told you so,’ but I think those words echoed in her mind regardless.”

So when Shyamala said to her daughters that you exist in the “context of all in which you live and what came before you,” she was likely reflecting on her own life. She had married the man of her choosing for love, for freedom, and for autonomy. Later, however, years after her divorce, Shyamala probably saw that she had been, as her famous daughter would put it, rebelling against her past as much as charting a brand-new destiny.

Even in the private intensity of her romance, which Shyamala experienced as her own will, the past loomed. She hadn’t realized how difficult marriage could be. Later, she must have asked herself what might’ve happened if she’d followed her parents’ recommendation and accepted an arranged marriage. That path might have lessened some burdens, given the context in which she had been raised, lived, and all that came before. Maybe her life would’ve been different if she’d relied upon people “more emotionally mature” to help with the big decision.

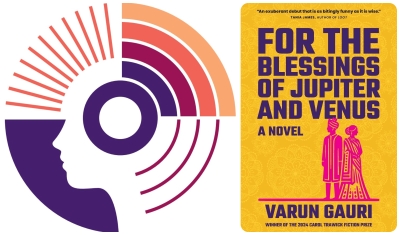

My novel, For the Blessings of Jupiter and Venus, explores these themes. Meena and Avi, a young, liberal-minded couple, have dated many people yet still choose an arranged marriage. They eventually learn that the distinction between arranged marriages and “love marriages,” as they are called on the Subcontinent, is blurrier than many imagine.

Couples in arranged marriages sometimes fall in love, or hope to, especially if they are modern. (A pair of my own relatives who had an arranged marriage report having had a secret tryst before tying the knot.) And couples in love marriages sometimes find that the passion they once experienced as freely chosen was actually influenced, even determined, by the context of all in which they lived and what came before — their cultural backgrounds, economic class, social networks, childhood experiences, and inner psychic forces (and nowadays, certain algorithms).

The fact that none of us falls from a coconut tree isn’t only a point about the limits of libertarianism. It’s also, maybe primarily, about how our most intimate experiences of personal freedom may sometimes be illusory.

[Editor’s note: This piece is in support of the Inner Loop’s “Author’s Corner,” a monthly campaign that spotlights a DC-area writer and their recently published work from a small to medium-sized publisher. The Inner Loop connects talented local authors to lit lovers in the community through live readings, author interviews, featured book sales at Potter’s House, and through Eat.Drink.Read., a collaboration with restaurant partners Pie Shop, Shaw’s Tavern, and Reveler’s Hour to promote the author through special events and menu and takeout inserts.]

Varun Gauri was born in India and raised in the American Midwest. After studying philosophy in college and public policy in graduate school, he worked for more than two decades on global poverty and human rights, publishing academic articles and books on development economics and behavioral economics. He now teaches at Princeton University and lives with his family in Bethesda, Maryland. His short fiction was nominated for a Pushcart Prize and was recognized in The Best American Nonrequired Reading. He was a summer writer-in-residence at Washington, DC’s the Inner Loop. His debut novel, For the Blessings of Jupiter and Venus, won the 2024 Carol Trawick Fiction Prize and was selected for NPR’s Books We Love 2024.