The study of poetry is anything but linear.

Learning to read and write poetry isn’t a linear process. Though one wouldn’t necessarily be required to watch “Dead Poets Society” to understand this fact, many folks certainly discovered it that way.

I recently watched the film with my family during our annual vacation to Ocean City (well, most of my family, anyway; my daughter bowed out after the first 10 minutes), and I was reminded of the genius of Robin Williams as wisps of nostalgia brought me back to when I first saw it as an adolescent. I couldn’t have imagined then that I’d grow up to teach students how to write poetry, and that most of my professional life would be engaged with that corner of pedagogy.

Carpe diem, indeed.

Whenever I walk into a new semester of teaching a poetry workshop, I have a set of strategies and questions and quotes to pull from that have served my classes well over more than a decade, but I also approach each new class somewhat like a meteorologist trying to predict the weather. In this case, the weather is akin to the many emotional responses, dialectical death-matches, or intellectual inertias that might arise from students who are trying to seize not the day, exactly, but their own imaginations. Each student’s relationship to language is different, and because I believe poetry’s purpose is to renew that relationship, it can be a joyously fraught endeavor to predict their emotional “weather.”

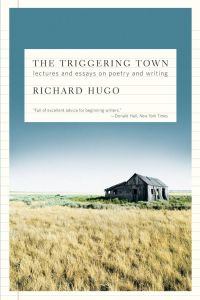

I still present some of the texts that worked for me as a grad student, like Richard Hugo’s The Triggering Town or Denise Levertov’s “Some Notes on Organic Form,” but I’m also aware that my students’ loci of relationship to those texts will all be different. Even though I teach in a grad program made up of a diverse range of ages — it’s not uncommon for a third of the class to be 15-20 years older than me — I generally believe everyone begins the lifelong apprenticeship to poetry in a similar place. How quickly or slowly they move forward in their learning, however, varies wildly.

What a student reads, how a student reads, how open the aperture of their curiosity, how much they believe can be learned and taught — all of these factors alter the pace at which they progress. But those progressions are not a straight line. Even to say, “Two steps forward, one step back” would be inaccurate. It’s more like the progression of a waltz with a lover: They glide in circuitous movements across the whole area of the dance floor — if it’s empty — or in a tight circumference if it’s crowded. Learning to write poetry is about how much your feet can remember and how much your attention can be held in the presence of another person’s attention. Circles on circles.

To leap to another metaphor, it’s better to be Magellan than Columbus, but there’s no shame in being a child on the shore, dreaming of faraway worlds and drawing ships in the sand. We must all learn that, when we learn, we move beyond the edge of our knowledge into a new “diem” to “carpe.” In that way, we can let go of the notions of being unworthy, overlooked, or untalented.

In other words, just keep moving, even when the horizon is “sawed in half,” as Walcott wrote. Even when others can track your progress. And even when other professions seem more full of certainty. Just keep moving into the presence of poetry.

Steven Leyva’s latest poetry collection is The Opposite of Cruelty.