A poem a day keeps despair away.

Like most self-care regimes, my reading is ritualized. I must finish any book I start. I have at least four books in rotation at all times: a poetry collection, a short-story collection, a nonfiction book, and a novel. My first leisure reading of the day is always a poem, a benediction to the power of language; grace before a fine repast; a blessing on my grasping mind; a tribute to the poets who marry form to thought and words, exploring the outer edges of human communication.

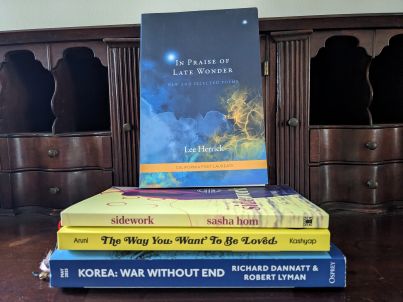

Currently, I am reading In Praise of Late Wonder: New and Selected Poems by California Poet Laureate Lee Herrick, a Korean American adoptee whose work probes the liminal space between meaning and the mysteries of the universe. He writes lovingly of California and Korea, stars and food, sound and light, and the parents who raised him and the parents he’s never met.

Here’s an excerpt from his poem “Elegy,” dedicated to Phillip Clay, born in Korea and adopted to the U.S., only to be deported as an adult because his American parents neglected to naturalize him. Back in the land of his birth, now a foreigner without family, language, or knowledge of the culture, Phillip took his own life:

In my dream, when you fell through

the sky from fourteen stories high,

all burning paper, your body broke

into a hundred flowers and floated

into the clouds. The moon and stars: still.

My nonfiction book is usually about the sociological structures behind relinquishment and adoption, a history on a subject of interest to a writing project, or a memoir. At present, I am perusing Korea: War Without End by British military scholars Richard Dannatt and Robert Lyman, a chronological account of the Korean War with the thesis that the Americans dragged on the military action for years, attempting to win an unwinnable war. Racism also played a role, as the Americans underestimated the fighting power of both the North Korean and Chinese troops (and mixed up them with their South Korean allies, to fatal effect).

Though respectful of Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s military genius, the authors lay the blame on him for waging WWII-style warfare of complete victory in a new kind of war in a new kind of geopolitical world. According to the authors:

“MacArthur suffered from several character flaws, by far and away the worst of which was vanity. To compound this problem, he had spent his entire career surrounding himself with sycophants, unwilling to bathe in anything less than constant adulation.”

Though I’ve always been devoted to short stories, now that I’m working on my own collection, I read them with a more critical eye. I’m currently making my way through two collections. The Way You Want to Be Loved by Aruni Kashyap, a writer from Assam in northeast Indian, features stories set in India and America, with themes of human connection and the sometimes unbreachable distance between the storyteller, the story, and the audience. In “Skylark Girl,” Sanjib, an Assamese writer at a literary conference in Delhi, confronts the expectation that he should write about the traumatic history of his home state after he reads his story, a retelling of a folktale.

A woman who’s writing her doctoral thesis on literature from Northeast India asks him why he “decided to write about this magical world, instead of the insurgencies, the violence, and the more immediate, the more topical stories? He was surprised because no audience member had ever asked him a question like that before. When she ended, the moderator said, good question, and a lot of people clapped, as if the woman was calling Sanjib out for doing something terrible.”

The other book is The Collected Short Stories of William Faulkner. When a writer is anointed with literary greatness, even drivel is profitable, as enterprising publishers (in this case, Vintage Books) are well aware, selling doorstoppers to college students (with Faulkner, to my brother at Princeton, though only 11 of the 42 stories were assigned). I’m soldiering through the racism, misogyny, and wearyingly repetitive style of this 900-page work because, as I mentioned earlier, I religiously finish what I start.

Ah, but to wash my soul clean, I turn to Sidework, a novella by Sasha Hom that follows “a homeless Korean American adoptee in braids” through one day (January 5, 2020) at work as a waitress on the morning shift, interacting with co-workers and customers while worrying about her family, who’ve been living in a van in a megastore parking lot since the Northern California property where they’d been part of an intentional community burned in a wildfire and was then sold to a wealthy newcomer. With a raptor’s eye for detail, the author offers an elegiac portrait of a society teetering on the edge, threatened by climate change, economic inequality, and human indifference:

“Living in a wall tent is way nicer than living in a van, is another line I feed my regulars, unless there’s a wildfire.”

There’s a metaphorical wildfire of ultranationalist fascism threatening the world right now, along with the very real fires of climate change. Every day is a bad-news day. Every day, I seek sanctuary in a poem, the genuflection that begins my ritual of self-care.

Alice Stephens is the author of the novel Famous Adopted People.