Long-ago postcards bring to life the baby brother I barely knew.

Despite the July heat, I rooted around in the summerhouse attic, seeking the box of my mother’s correspondence from the 1950s discovered years ago while cleaning out my parents’ home. With neither the time nor heart to read through it then, I remembered putting it aside and storing it here, unless I’d lost or discarded it in the haste and haze of that moment.

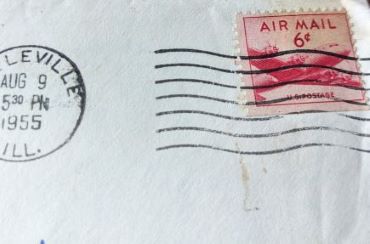

Success! The box held a few letters, lots of postcards — not picture postcards but USPS pre-printed ones (postage: two cents) and improvised ones on index cards. Sometimes, Mom crammed several homemade cards into an envelope (airmail: six cents). Most were addressed to her parents in Illinois. The summer of ’55, she, my little brother Hugh, and I visited my grandparents. My father stayed back East to work. She sent cards to him almost daily.

Hugh would’ve turned 70 on July 27th this year. We were 17 months apart. He died March 1, 1956, four months shy of his second birthday. I’d just turned 3.

He died suddenly of an acute attack of an intermittent gastrointestinal condition. Even with attentive pediatric care, the cause and severity of his problem was undiagnosed or undiagnosable in those days. That’s all I know. Every family has no-trespassing zones.

Many children die — of illness, accidents, natural and manmade disasters, and violence — even now in the middle-class suburbs of this First World country. Ours is not an extraordinary story. Life continued; my brother Donald was born in ’57. We’ve had more joy than sorrow.

My parents rarely spoke of Hugh. Albums of black-and-white snapshots document his brief cameo appearance. The only remaining immediate family member who knew him, I don’t really remember Hugh. He left a flickering shadow — a lost-boy shadow.

I sorted the cards by date, postmark, or best guess, a little like beginning research for a story. But I was shuffling these cards for a game of solitaire. The objective: Find Hugh.

Mom’s postcards proved to be field notes from the communal life of young families on a small college campus teeming with children. Finances were tight, and so were friendships in the babysitting cooperative (despite the annual competitive scramble among junior faculty for campus housing).

A primary-school teacher before having kids, my mother was fascinated by child development. Here’s a sample daily bulletin to her parents. Hasty, tiny, almost illegible cursive fills the index card:

3/28/55 My dears we watched it happen. On his 8th month birthday Mr. Hugh decided he was through with being so-o-o good and agreeable. Really one moment he was happily playing with his rattle & the next he took off in hot pursuit after Ellen clamoring for the blocks…I may come to prefer my constant little skirmishes with E to the occasional full dressed battles I fear I will have with Who. Sorry I even used those words for they remind me of the world situation. How could our state dept. have gotten us in such a mess over those foolish little islands [Formosa].

Until reading the cards, I never knew I called him “Who.” The small, intimate detail feels revelatory.

The summer of ‘55, Mom traveled by train from Philly to St. Louis with two toddlers, luggage, a big stroller — and a typewriter! Even typing single-space, missing Dad, she often had too much to squeeze onto one card:

…This calls for an envelope so I can write a few more lines. Who is such a climber and once he makes a leap…he thinks it’s easy…Tonight the chair was several inches further away so he got a hard bump. It’s like having a blind person in the house. Once the tears stopped he was up again.

Hugh’s first birthday, July 27th, his cake sported a full-size red taper:

He quickly grabbed the candle and began brandishing it like a club and just beating heck out of his cake…We just stood by helplessly and Grandpa shot on.

The photo album only shows Hugh beaming over his intact cake. Late to the forgotten party, I now enjoy his exuberant outburst of appreciation. Bold, kinetic delight was his style. Mom describes us riding a miniature merry-go-round at the grocery store:

[Hugh] brushed aside our restraining helpful hands and grasped the saddle horn with one hand and waved merrily to us with his free hand…Ellen wasn’t afraid but held tightly…admonishing H to do likewise.

At the house, I tend to stay close. Hugh crawls alone across the lawn to my grandfather’s workshop:

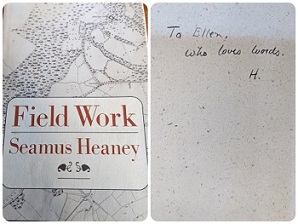

[Is he] more venturesome or just too young not to know better…However if H strikes out E always accompanies him chatting gayly to him as though they were communicating perfectly. He says MaMa and that is all that can be called English.

We were communicating perfectly — in sibling language. What would we have talked about when he spoke more English? It’s unknown, unknowable. After his birthday, only six months of correspondence, six more envelopes remain.

The shortest month, February 1956, yields the thickest pile of cards — flash reports of so much growth and change that words often fall off the margins. Here, it’s time to hand down my outgrown tricycle:

2/10/56 This weekend we are going to buy trike blocks. Once H becomes adept at using the pedals he may take off for regions unknown.

We visit the school where Mom taught before I was born:

2/22/56 The principal invited us all to stay for lunch. What a crazy hilarious time we had in the noisy lunchroom. The louder it got the better H liked it — after he had covered himself & the rest of us with spaghetti, he wandered around among the big kids never giving us even a glance…E is enjoying it all more in retrospect that she did being in the din.

I still enjoy din more in retrospect. She nailed my character so accurately, I trust her observations of Hugh.

Two weeks after I turned 3, it was my friend Nany’s third birthday:

2/28/56 E left for the party looking like a dream in her Becky S. white gloves — I hope she acted ½ so well as she looked…

Five-year-old Becky S. was an admired Older Girl. It’s likely I lived up to the hand-me-down gloves.

Mom signs off on this last day of February, describing Hugh’s bedtime:

Who has to be read to before you put out the light at night. No one has ever seen a 1 ½ year old sit for as long for stories…xx Nelle

The card is addressed but unstamped. Never mailed.

There is no card for March 1st, the day he died. No cards at all for March. Silence, until Mom and I visit friends in Boston at the end of the month. She writes a long letter to my father:

…Hugh found all of life to be an interesting, pleasant and rather exciting adventure…I feel I owe it to Hugh to try to sharpen my senses and responses so that I get the most out of the present big and small moments…

But that’s what she’d been doing all along — a prescient enjoyer, recorder, sharer of the moment.

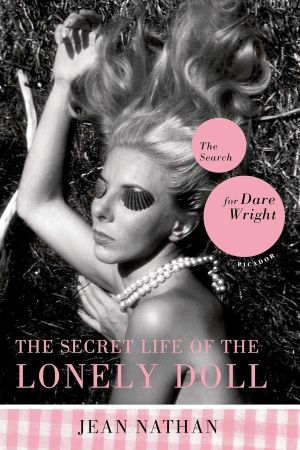

Hugh ventured off to regions unknown. Thanks to my mother’s jottings, there’s now a boy attached to the flickering shadow. Pictures are often worth a thousand words, but some words are worth a thousand pictures.

Ellen Prentiss Campbell’s collection of love stories is Known By Heart. Her story collection Contents Under Pressure was nominated for the National Book Award, and her debut novel, The Bowl with Gold Seams, won the Indy Excellence Award for Historical Fiction. Her novel Frieda’s Song was a finalist for the Next Generation Indie Book Award, Historical Fiction. Her column, “Girl Writing,” appears in the Independent bi-monthly. For many years, Campbell practiced psychotherapy. She lives in Washington, DC, and is at work on another novel.