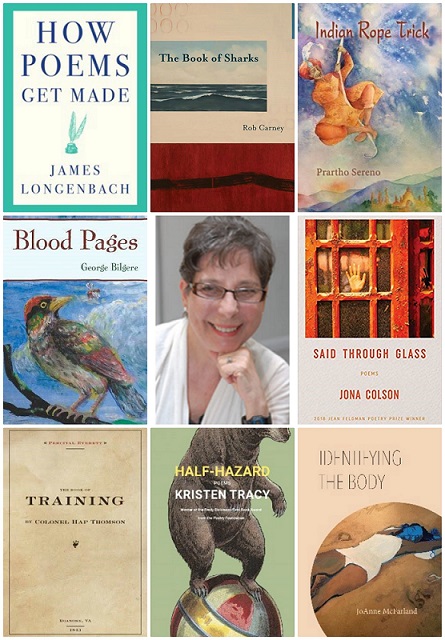

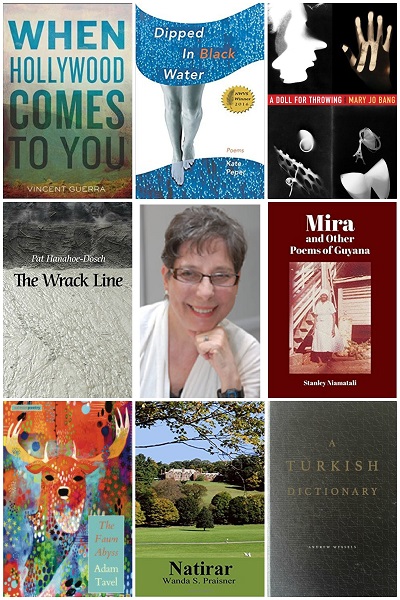

New collections to make life more lyrical.

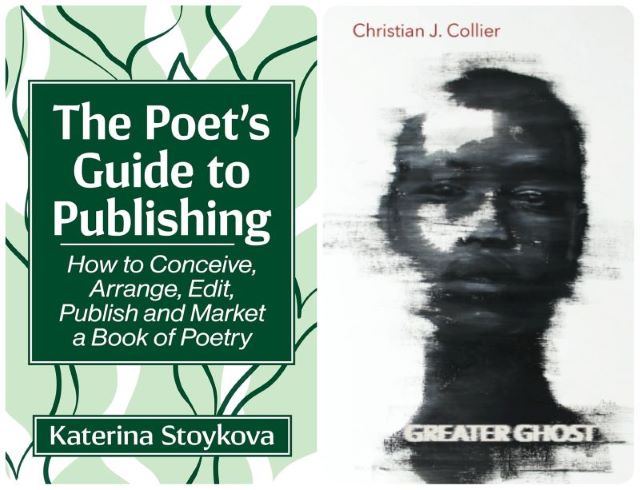

Katerina Stoykova adds to the canon of how-to handbooks with The Poet’s Guide to Publishing: How to Arrange, Edit, Publish and Market a Book of Poetry (McFarland & Company). Pragmatic in its advice, conversational in its tone, and detailed in its observations, it’s a natural companion to Jeannine Hall Gailey’s PR for Poets: A Guidebook to Publicity and Marketing (Two Sylvias Press), but with a much broader focus. Stoykova’s book addresses the need for demystifying the publishing process in ways that are particular to poetry publishing, and it draws on her years of experience teaching a Poetry Book Boot Camp.

The book is organized into five parts — Concept, Arrangement, Revision, Publication, and Promotion — meant to track the entire journey of a poetry book being released into the world. Early in the first section, Stoykova emphasizes the meaning of “release” as “a way of disconnecting from [the book], partly because you need to release control,” rather than focusing on its more common meaning in this context (i.e., making a work publicly available).

Many creative-writing teachers are likely to nod in agreement with this foundational distinction, having walked emerging writers through various kinds of thesis projects. Additionally, the sentiment feels hard-won and clearly the result of Stoykova’s own experiences seeking publication, which she refers to often.

Each section includes anecdotal excerpts from former attendees of Poetry Book Boot Camp, and while their inclusion certainly grounds the book in lived experience — and rhetorically argues that the ideas presented have practical applications — I found their frequency a tad distracting. Readers’ mileage will vary depending on where they are in the publication journey.

Along with the detailed information in every section, I really appreciated that each one ended with a “Qualities Needed at This Stage” primer, which served as a metacognitive check-in with the reader and perhaps a bulwark against the inevitable “I tried all this, why doesn’t it feel like it’s working?” response that some poets will have. For example, in part one (Concept), Stoykova writes that the qualities needed are “Tolerance for ambiguity” and “Willingness to waste effort and time.” If those sound counterintuitive in the opening stage of a book, I promise you that Stoykova makes a persuasive case for what she means, and I’ve seen her points reflected in my years as a teacher in an MFA program.

Something that felt new here was the metaphoric application of Stoykova’s background in computer science to help demystify the publishing process. I was especially intrigued by her use of “Metafiles” as a practice that felt a bit like textual vision-boarding. I also enjoyed the revision checklists, the conversation on choosing titles, the straightforward approach to explaining the relationship with publishers, and more generally, the warm heart the book exudes.

How-to guides can often sound condescending when they don’t mean to be, or myopic beyond all recourse, yet Stoykova avoids these pitfalls gracefully and, at times, with genuine humor. She brings her multilingual and international publishing background to the fore in a way that feels inclusive. I think a range of readers will find this book teachable and re-readable.

*****

Christian J. Collier’s debut full-length collection, Greater Ghost (Four Way Books), is a generous exploration of grief, elegy, erasure, and auditory echo. Reading this collection felt akin to walking and listening to a lyrical docent’s tour of a textual memento-mori. Each poem echoes the sentiment of the book’s final line, “I’ve yet to stop feeling the roots dying beneath my feet.” I want to draw attention to that ending because many of the poems feel like the “backwards planning” often employed in various pedagogies. In other words, the book is trying to teach us something about grief — perhaps something we already know but have forgotten — but it does so with the heartfelt searching of someone who isn’t sure there are any answers to be found.

The echoing subjects of miscarriage and the unjust death of folks killed by police are mirrored in the euphonic attention Collier pays to his lines. An early poem, “The Compline,” begins with a set of couplets that are indicative: “Between us, there are one hundred one / umber haints in our home. // In bed, we discuss / our future, our children woven in myrrh, sitting.” If sonic pleasure can be viewed as an act of earned trust between poet and reader, then Collier is a consistent, trustworthy voice. And trust is so important in a book organized without section breaks (so that the reader must confront grief’s relentlessness).

Plenty of desire, a natural cousin to grief, exists within the movement of this book, too, reinforcing what we live for and what we have to lose. “Ghost [Retrograde]” is an early example of such a poem and also establishes a titling convention repeated throughout the book, where “Ghost,” followed by a bracketed parenthetical, creates an antiphonal effect. Simply reading the table of contents can help a reader catch that vibe. Many may see the book in conversation with Marie Howe’s What the Living Do.

Collier also makes use of a light touch of erasure, redacting the names of certain folks who’ve died, while addressing others with an epistolary diction. Thus, loss is aggregated, becomes exponential in its suggestion, and becomes a literal black mark on the page, seen and unseen. This hyper-visibility and invisibility is a ubiquitous feeling among many Black Americans, and I appreciate how the book allows us into that experience. The double erasure is a way of making greater ghosts.

Other echoes abound throughout the collection. More than once, the speaker of these poems asks some version of, “Did you feel it?” or “You feel it, don’t you?” A near-devotional questioning of God is omnipresent but never in a way that feels exclusionary. The South as a landscape made of language grounds the images in specificity and inventiveness. And though I believe the word to have nearly lost all meaning, it is appropriate to say the poems feel authentic, by which I mean they embody what Czesław Miłosz meant by “language is the only homeland.”

I wholeheartedly agree with Gabrielle Bates’ assessment of the book, which she wrote in a blurb: “Here are poems populated by the dead, pulsing with life.” Which is to say, the book is optimistic — not about the state of the world, but about the reparative power of poetry itself.

Steven Leyva’s poetry collection is The Understudy’s Handbook.