New collections to make life more lyrical.

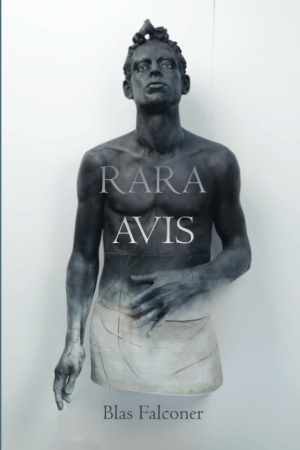

Reading Blas Falconer’s Rara Avis (Four Way Books) is like listening to an orchestra tuning up, the care of each (lyrical) instrument searching for the slight variances that bring harmony, insight, understanding, and, dare I say, awe. But it’s an awe made of subtext to be sure, or as Sandra Beasley wrote in her blurb for the book, “Falconer could teach a master class on lyric subtext.” I agree, but its greatest pleasure was how it was able to touch the personal, the idiosyncratic, in me as a reader.

As someone with type-II diabetes, for me to encounter both the fragmentation and the subject of the early poem “Pancreas” is startling, doubly so as it is a poem that announces the father figure who haunts the book. For my family, diabetes is generational, and so two touchpoints converge in the content. But it is the deft use of form, of interesting enjambment, that makes the poem amplify its heartfelt pain.

Fathers and sons pull and push in the tension of couplets, such as in “Sons,” where Falconer writes, “Is not, Is too they argued as I floated like / a dream through the dark above them,” describing the rhetorical tug-of-war among siblings trying to prove whether another sibling is faking sleep. The form in that poem also enacts intervals of movement — back and forth — which are taken up, too, by other poems in the collection, even when Falconer moves to tercets.

In “Legacy,” I connect again with the dance of form and content, being the child of an immigrant and landing on lines such as: “language, boxed / with whatever else // she can’t take, / coming to break me / faster.”

Migration toward and away from one’s family is an inescapable process, but it’s one that Falconer presents to readers with precision and beauty. I say precision to capture how acute, how pointed, the syntax feels, but don’t mistake that for stoic distance. There is plenty of passionate feeling just below the surface of these poems, often explicitly breaking out into an unfiltered, hard-won wisdom.

Many readers may recognize a kinship in these poems with the tenderness of Li-Young Lee’s early work in Rose, but also with some of the inventiveness of Tomás Harris’ Cipango. And tradition, or more specifically, heredity is so vital to the book’s tensions that it seems to be prismatic in its understanding of those two words. Rhizomatic would not be an overstatement here, which makes it all the more amazing when the book feels intimately personal. Any parent, any child, anyone interested in literature should read the poem “My Son Wants to Know Who His Biological Father Is.”

This feels like a moment when the country could use the radical clarity that poetry provides, the human intelligence at work, the language awakened to itself. Falconer achieves all of this without hyperbole’s seduction or sentimentality’s insincerity.

The book opens with the title poem, “Rara Avis,” and ends with “The Hummingbird,” as if to position the reader between two wings in a body in flight, uncertain of where to land one’s grief. But this is the pleasure of poetry. Doesn’t it teach us how to mourn so that we’ll value having lived? I think so. And I think Blas Falconer’s Rara Avis leads us toward a flight home, to the heart.

Steven Leyva’s poetry collection is The Understudy’s Handbook. His new collection, The Opposite of Cruelty, is forthcoming from Blair in March.