New collections to make life more lyrical.

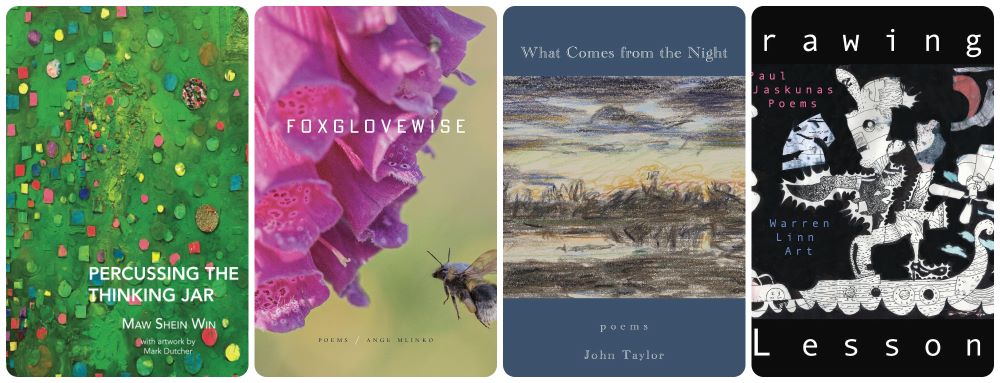

Maw Shein Win’s Percussing the Thinking Jar (Omnidawn) is comprised mostly of “thought logs,” a poetic form she devised to include declarative statements and fragments, phrases that come in threes, and occasional questions. They are interspersed with Sumi ink drawings by Mark Dutcher, and some are translated into Burmese by Kenneth Wong.

Win started writing these thought logs in 2020, so they reflect that slightly skewed lockdown perspective you recognize when you see it. Existential concerns exist alongside musings about goat rentals and practices like recording dreams. Win also plays with her mother’s linguistic distortions brought on by a stroke, and the hole left in her life by the death of her cat, Bokchoy.

She combines textured linguistic rhythms with unusual juxtapositions and mixes flashes of vulnerability, even banality, with moments of clarity. I found myself returning to this one:

mud, jug, poison stream

holding my head with my hands

anxiety spills, suspended atlas

that time I got so high I, I

blurred pilgrims, rigged systems

tossed across the room

Immersive theater, verdigris promenade

erratic visitations, my drawn-in brows

thorn, pheasant

Her blunt, declarative statements put me in mind of Michael Palmer’s autobiography poems. But she also sprinkles her work with humor. For example, in “Blood Pressure Logs,” she writes:

C & I go to Marshall’s one week before my surgery date. I want something fuzzy to lounge in, new pajamas patterned with pink cats in space. Experience landfill guilt.

There’s a certain vulnerability in Percussing the Thinking Jar, but at its core, it’s resilient. We’ll find our way forward, she seems to suggest, and we’ll do it while writing poetry.

*****

Ange Mlinko’s Foxglovewise (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) is a little puzzle-box of a collection that, like her previous book, Venice, deals with overlapping realities and reflections brought on by travel.

Her poems are structurally formal with complex meter and rhyme schemes. But within these constraints, she meanders and plays with words, integrating surprisingly disparate elements.

The first poem, “Tarpon Springs, Epiphany,” is a layering (and there are several layers) of Maria Callas’ experience in Tarpon Springs, Florida, with the poet’s own experience, during which, in an “elemental paradox,” rainfall threatens to ruin a Greek Orthodox “crucifix dive” into the bayou during Epiphany.

In the next several poems, Mlinko is in Scotland but “in two foreign countries at once, by turn.” While walking through a graveyard and sounding out names on the tombstones, she’s also listening to The Iliad and its names on her headphones.

In another exploration of paradox, this one set in Scotland, a friend recommends that she search for a wyvern (a two-legged dragon), but an app gives her “a fenced in graveyard as a shortcut.” She finishes the poem:

The grammar of romance demands ellipses, perhaps...

As “loan” for “lane” gets at the glamour (same root,

In Scots) of a temporary state. It’s not on the maps.

Another poem, “The Empire of Flora,” begins with a friend talking about landscaping and gradually transforms into an exploration of Nicolas Poussin’s painting of the same title.

In “Flamboyance,” we find a flamingo “standing on his honor, with one foot./He has lost his flamboyance —/which is what we call Flamingo flocks.”

But you might miss seeing this flamingo, just like the wyvern from the previously cited poem was missed.

You can’t tell if it’s smoking or misting —

the vision field smeared as with ointment.

You’ll reach for your binoculars

to catch fire and water coexisting.

In these poems, the pleasure of discovery comes with patience. Mlinko leaves hidden keys to spaces carefully constructed for wordplay and contemplation. But it takes time to find them.

*****

I first encountered the work of John Taylor through his translations of Italian poet Franca Mancinelli. His new collection from Coyote Arts is a series of short poems and notebook fragments. Its title, What Comes from the Night, refers to a notebook kept on his bedside table.

His inspiration is the natural world — glaciers and gusts of wind, what the shifting tides reveal, and passing clouds overhead, which “reply/with their journey.”

Taylor has lived in France for years, and some of these pieces were written in the Loire Valley, which is close to my heart. Particularly lovely are his minutely observed “portraits” of yellow wildflowers. Here’s one on St. John’s wort:

in your collapse you become

what is left over

in the darkest soil

to grow hands again,

to open them

As Taylor immerses us in the subtle dance of natural forms and elements, external life becomes inner life:

snow sparkles

in the air

in the one

life

outside the windowyour thoughts join the real

flurries

on the dark branchall now one

for one moment

It’s as though, with these poems, we find our place in the continuity of being.

*****

As soon as I saw Warren Linn’s cover of Drawing Lessons (Spuyten Duyvil), I knew this book was right up my alley. It’s a collaboration which began when Paul Jaskunas wrote a poem inspired by one of Linn’s collages at the Maryland Institute College of Art, where both taught.

Their collaboration has a kind of “Saul Steinberg meets Kenneth Patchen” quality. The artwork in the first section, “Boat Songs,” is primarily black and white, mixed media, and collage on paper, while the “Portraits” section includes colored acrylic and collage.

Jaskunas explains that his poetry complements the artwork with “a similar improvisatory disposition to jazz composition.” His light touch, with its edge of the macabre, reminds me of Serbian poet Vasko Popa — specifically, that marvelous translation by Charles Simic of Popa’s “Give Me Back My Rags.”

Here’s an excerpt from Jaskunas’ “Wandering Fools,” which accompanies Linn’s collage “DinoDino”:

I miss my face

If ever it washes up in the waves near you,

do fish it out, dry it off,

keep it clean in memory of me.

Perhaps you could display it

in one of your time’s museums

where the wise may muse

upon one used-up face,

and the fates of all us wandering fools.

Drawing Lessons is thoughtfully arranged and thoroughly immersive. I went from poem to collage and back again, absorbing each piece in turn. But by the time I got to “The Cloud,” in the final pages, something had shifted. The poems had taken on a life of their own, and it no longer mattered which piece had inspired which.

Amanda Holmes Duffy is a columnist and poetry editor for the Independent and the voice of “Read Me a Poem,” a podcast of the American Scholar.