New collections to make life more lyrical.

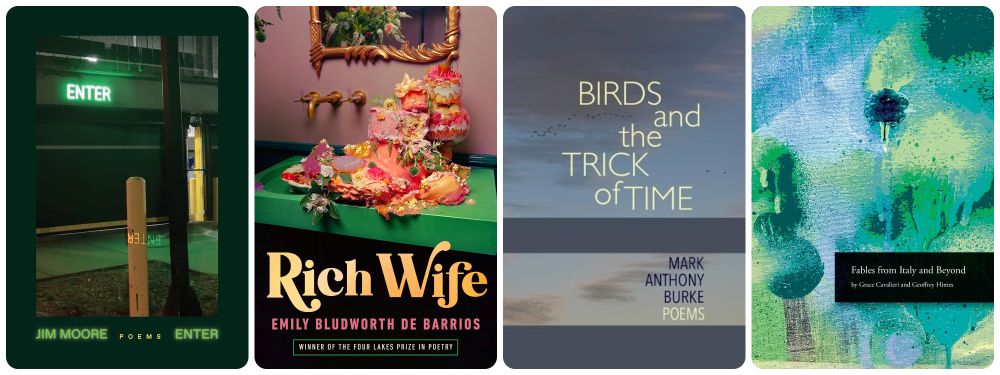

Enter (Graywolf Press), Jim Moore’s wise new collection, demonstrates that, at 79, this poet is still at the top of his game. He’s reached a place where hope is now irrelevant. “How strange,” he writes, “that the subject of life is death.” It’s as if he’s on a bridge looking into the deep and realizing there’s nothing left to fear. In the first poem, “Prelude,” he writes, “Everyone / everywhere is just holding on.”

It’s astonishing how adroitly he moves between seemingly disparate topics in the space of a single poem. Take “Mother,” for example. In fewer than 30 lines, he gives us a cat called Mother but also the death of this cat, along with the trauma of a childhood rape carried into old age. He finishes by addressing his wife, Joanne, who loves the smell of flowering lindens as much as he does. She stands beside him to “stare down into the black current / which has reached flood stage / and sweeps everything before it.”

Several poems are set in Italy, specifically in Venice and Spoleto, where he lives part time. These places, full as they are of history and elderly people, have a knack for reminding you that time runs out. One poem is entitled “Everything Is Not Enough,” a refrain he returns to repeatedly. But he’s managed to find a comfortable place in these poems for despair to exist side by side with beauty.

There’s so much grace and tenderness in his work, and not a shred of self-importance. The poem “How to Come out of Lockdown” finishes, “nothing in this life / is asked of me except to remember how small I am.” Elsewhere, he tells us:

I need to stand for something

beyond my own defect. And that would be

what exactly? The word humility

comes to mind. If I make it

farther than that, I will let you know.

This collection is largely about finding something in life to sustain you through the sense of its ending. Moore puts no stock in the afterlife, either. Each line in his poem “To Be” ends with a mockingly emphatic exclamation point, as in: “To know right from wrong! / Sunlight from shadow! / Life from death!”

Perhaps my favorite, illustrative of the mood throughout this poignant book, is a short poem called “No More Paddling Tonight”:

A beached kayak sits under a streetlight.

No more paddling tonight! Say manatee

and dream. Since an ode always sleeps inside

an elegy, the paddle shines in the light. Its dark wood

still wet from the day that once was.

*****

Gelatinous tiers of pink and orange cake flow across a bright green platter on the cover of Emily Bludworth de Barrios’ new collection, Rich Wife (University of Wisconsin Press). “Grandmother Worship,” her opening poem, has a 1950s aspirational flavor with its pillbox hats and purple carpets, lipsticks, and hair dryers shaped like giant eggs. But a flair for kitsch is only one of the tools in this poet’s arsenal. A wicked sense of humor is another. A third is a talent for astute literary and mythological analysis. As de Barrios delves into the coveted assets of the so-called rich wife, the reader is quickly caught up in its pitfalls.

By the third section, her exploration of 19th-century rich wives and daughters (Zelda Fitzgerald, Edith Wharton, and Virginia Woolf among them) reveals a disturbingly sinister undercurrent. Quotations are recontextualized. “She made no reply but her face turned to him with the soft motion of a flower.” Later, we get such juxtapositions as, “(Without some money) (to carry on) / The rich wife nods to the women who lived destitute / “much deteriorated.”

Other lines read like nesting matryoshka dolls:

Inside the hatred of the rich wife

Is a hatred for wealth

And inside the hatred for wealth

Inside the rich wife is a little pocket to stuff a hatred for women

Yes, there’s something about the concept of a rich wife we all love to hate. We instantly recognize her artifice, ambition, and inherent lack of meaningful authority. We also “relish the failed attempt.” Maybe it’s because we know she’s inauthentic. And how about this for a killer line: “Imagine a doll that has a person inside it.”

The tone shifts in the final sequence, a lively exploration of the Greek goddess Hera and the qualities of vengefulness and jealousy she embodies. All Hera’s impulses flow from her identity as Zeus’ wife. But we come to see that although she is the archetypical rich wife, Hera is also intrinsically powerless.

*****

In Mark Anthony Burke’s Birds and the Trick of Time (Circling Rivers), memories surface with the appearance of birds. “They glide from tree to tree, / compile their inventories, / drift over the swath of light.”

Sheep farmers and itinerate workers populate his poems. There are early mornings in the mountains, late nights playing cards, odd jobs, temporary lodgings, winter preparations. Travelers sleep in tents and on benches, scavengers sift through dumpsters, and the birds scavenge, too.

His overarching subject is the gap between those who pull away from this rural world and those who remain, as well as the gap between what is said and what is listened for. Men here find it hard to talk, but listening lies at the heart of these poems, and it falls to the poet to read between the lines.

In “Paper Man,” one of my favorites, the speaker discovers his partner’s infidelity as he wrestles with an armature for a papier-mâché sculpture. It becomes a poignant metaphor for his emotional machinations.

In “Living on the Light,” waxwings flying south occasion the memories of an elderly man whose wife left long ago. He “stayed to do what he’s always done”: canning preserves. “He steams out the moist air / The weight of the world / Pressing the lids tight for years.”

This is an evocative and emotionally complex collection. But all the poems are composed the same way, in short lines running down the page with no stanza breaks. I would’ve welcomed some structural variety to indicate shifts in mode or perspective. Even so, I returned several times to such delicately rendered verses as “Prairie Lightening,” where a hike into a valley as the clouds gather becomes the setting for a painful disclosure. The tension lies with the aloneness of both speaker and listener here, as well as in the intimacy conveyed by what is said and the attentiveness that continues into the ensuing silence.

*****

Fables from Italy and Beyond (Bordighera Press) brings together two beloved regional figures, poet Grace Cavalieri and music critic and poet Geoffrey Himes. Fables lend themselves beautifully to the repetitive patterns, metrical structures, and stripped-down narrative style of poetry. Section one is loosely inspired by Italo Calvino’s folktales, with some characters added, such as No Nonsense Nancy, and others embellished, such as Olio D’Oliva, whose antics thread throughout the poems.

Section two is a more modern take on folktales drawn from the poets’ combined backgrounds and imaginations. But in both sections, “A third note emerges creating a new chord, / never heard before yet strangely familiar.”

The poems predictably involve kings and queens, merchants and peasants who seek fortunes and outwit evildoers. They also include a fairy who “dived deeper into the poem than anyone had ever gone,” enchanted mirrors that lead to other states of consciousness, and doors that disappear, leaving no exit.

The stories in the second section are often told in first person and concern a twist in time. In “The Magician,” a ragged old man produces a velvet pouch containing a mouse in a fedora and a bonneted canary, who run up and down his arms. At the end, you find yourself in an enchanted but somehow recognizable space when:

Night after night, all we could hear

Were our mothers calling us home

For supper till their voices were

Faint as a whistle.

In “Mirror Mirror on the Wall,” the speaker tumbles from one mirror into another, finding herself transformed at every turn, until finally, in a mirrored ballroom:

I picked one with a glowing, golden frame and I somersaulted into

The mansion where I started. I could smell the mildew and the mouse droppings

The poem “Pretending” is about discovering self-acceptance. It ends:

You took off my mask

and kissed the mask underneathThe steam cleared in the bathroom mirror

And a face appeared.It was a face I had never seen.

It was mine, the face I’d always wanted.

This delightfully imaginative collection is suitable for all ages. I fully intend to share it with my grandchildren. Above all, though, these poems are restorative, reaching back to a world we recognize on a visceral level but might have almost forgotten. Just what we need on the night table during these troubling times.

Amanda Holmes Duffy is a columnist and poetry editor for the Independent and the voice of “Read Me a Poem,” a podcast of the American Scholar.