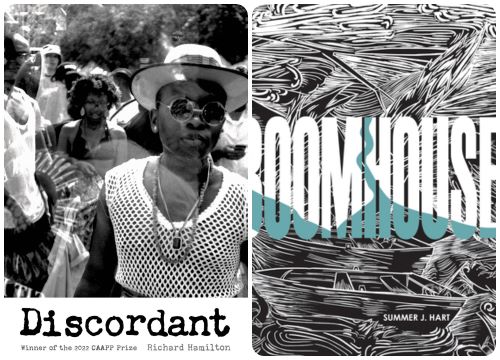

New collections to make life more lyrical.

More than 80 languages are spoken on the campus of George Mason University. So, what better place for a Day of Translation? It’s an annual event sponsored by the Alan Cheuse International Writers Center, which is named for the late NPR book critic, author, professor, and, back more than 25 years ago, my MFA thesis advisor.

This year’s opening discussion, “A Matter of Record: Reclaiming Histories Through Poetry,” brought together Polish poet Grzegorz Kwiatkowski and American poet and translator Randi Ward. Ward spoke with feeling of her West Virginia community, which has long endured the devastating effects of toxic chemicals in its soil and water. She read from her own work, as well as from her Nordic-language translations, which include an award-winning translation from the Faroese of Tóroddur Poulsen’s Fjalir.

Kwiatkowski recalled that, as a child, he used to walk with his grandfather in the wooded area surrounding the former Stutthof Concentration Camp in northern Poland. During the Second World War, his grandfather had been interned there. As they walked, the older man wept.

Years after the war, while in the woods with a friend, he unearthed masses of rotting shoes. They once belonged to thousands of men, women, and children killed by the Nazis. This horrifying discovery impelled him to push for the memorial museum that stands on the site today.

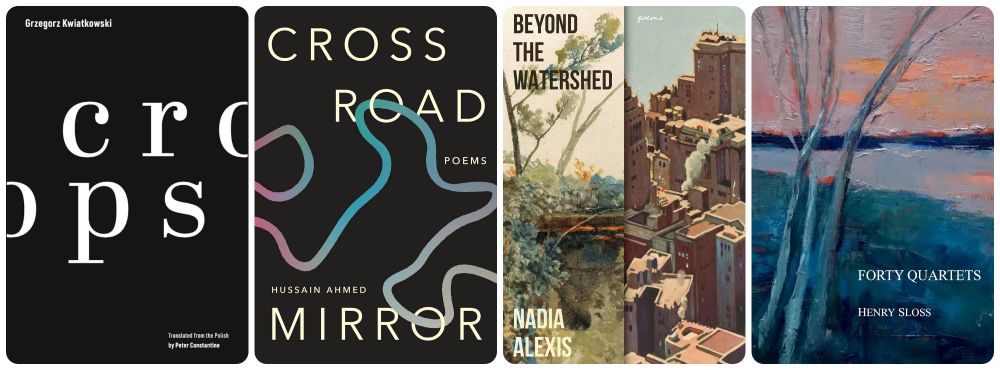

Kwiatkowski’s collection Crops (OHM Editions), translated from the Polish by Peter Constantine, is itself a memorial. It’s comprised of stark, declarative poems in the voices of farmers, neighbors, family members, victims, and apologists. The poems were inspired by transcripts and read like epitaphs, in the manner of Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology. Together, they form an unforgettable picture of a community marked by atrocity and denial.

Part I of the opening poem, “burning,” begins with names. Where are they, he asks, “all asleep beneath this soil.” Part II begins:

he had butchered eighteen Jews

he told me this in my apartment

as he installed my stove

The voice in some is so oblivious as to be darkly humorous. Take, for example, “Ernst Junger, b. 1895 d. 1998”:

War has let me down

Modern war

Has not met my expectations

It didn’t live up to its literary ideal

(for example, there were no horses)

Other poems break your heart. “Buzia Wajner b. 1937 d. 1943” begins, “I was six when I was killed/my sister Szulamt was four.”

Szulamt. The name sends shivers down the spine in its echoes of Paul Celan’s “Death Fugue.”

*****

What if the present was a no man’s land, a thin spine separating a vanished past from an unknown future? Nigerian poet Hussain Ahmed captures this sense of the present during wartime in Crossroad Mirror (Curbstone Books). Here, both the present moment and the individual selfhood seem to evaporate in the shadow of death.

Ahmed’s subject is the effect of war on civilians and refugees, on one’s sense of being and belonging. Prayers and rituals of honor are offered for the dead, and faith persists, although the prayer rugs in one poem are “shrunk with fire.” In another poem, a flood outside a prayer house washes the slippers left behind into a pool at the crossroads. In “Ashes,” the names of the dead are learned on the radio so that “Henceforth, all the dead would live in you.” In “Birthmark,” women in labor are cared for, but when mothers die in childbirth, other mothers take their place, individual faces blurring in the lantern light.

Anonymous though the dead may be, tending their collective loss knits together the disjointed fabric of everyday life. In “Unmarked,” a husband’s grave is simply “a mound of clay marked with Coca-Cola bottle,” his name scribbled on a scrap of paper inside it. What does it mean to be “unmarked” — to be as you were before you were marked by loss and grief? Or to become a photograph looked at by a stranger? I’ve been pondering this poem for days now.

Several pieces include the word “chimera” in the title. A chimera is something hoped for, but of course, it is illusory. One image variously repeated and played upon is of standing on the edge of a lake, dressed for a funeral:

In this picture I walked down the steps

Into the lake, dressed for a funeral

Except no one knew I died but the numbers rose

From the right corner of the TV screen.

Ahmed often employs caesuras of blank space to fracture his poems so that there’s a feeling of disjointedness to the narrative. In “Zuihitu,” he writes:

It was my exam week; it was Baba’s dream that I join the

Nigerian Army.

I was unbothered; I would rather die with a raffia pen in my

hands than a gun.This I could not tell Baba, for he stayed up in the night

and called on our ancestors to intercede

on my behalf.I heard him whisper into the night’s wind for days.

My hand wielded a pen and upheld the names of our dead.

Hussain Ahmed upholds his dead in these poems by honoring loss as a palpable force in the detritus of the present. I’ve been carrying this book around with me for weeks, a truly haunting collection.

*****

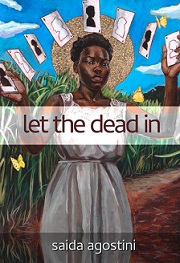

“There’s nothing like the thirst of Black girls who believe in their own dreams,” writes Nadia Alexis in Beyond the Watershed (CavanKerry Press). But realizing those dreams for herself has demanded the courage to confront generational domestic abuse.

An early poem, “Permission,” written in couplets, describes the terror that she, her mother, and her sisters endured at the hands of her violent father. It finishes:

Oh how i secretly wished him to dust

So we would have permission to breathe

The “I” here feels small and is written in lowercase. But the speaker gradually discovers that permission to breathe must come from herself. The poems are a journey toward granting herself that permission.

“Cassette-Letter ‘95” takes us back to pre-internet days, when her grandmother sends an audiocassette from Haiti to the family living in Harlem. Her mother takes the cassette from its envelope and inserts it in into the player. The granddaughter daydreams of her rural childhood as she listens to her grandmother’s voice assuring them, “Things are good in Haiti.” She visualizes the “mountains & the mountains behind them.” But when she looks at her mother, she sees that “the envelope in her hands in wrung out like a chicken’s neck.”

Mountains reappear further in the collection, as a symbol of female strength, when the girl breaks free from abusive partners and the example of her mother’s submissiveness. The sense of entrapment in such poems as “How to Be Friends with a Sex Worker” and “He Reasons” is powerfully communicated.

But interspersed throughout is a series entitled “Prayer to Èzili Dantò,” in which the last line of the first poem becomes the first line of the next. One recurring line reads, “people look at me in confusion & say I must like being held underwater.”

Èzili Dantò is a Haitian voodoo spirit who protects women and children. The poems dedicated to her are paired with photographs of a blurred female figure, sometimes headless. In the final photograph, a complete female form begins to come into focus.

The poem “Prey” marks another watershed moment, as Alexis takes control. “today I am guilty of becoming a falcon,” she writes. And later, “tonight I am Èzili Dantò’s child/armed with scarred vines & silver. /I strike & he falls like leaves under the/weight of a half-woman, half-mountain.”

“Beyond the Watershed” is a stirring debut chronicling a young woman’s passage from weakness to stability and self-respect.

*****

Let me now shine the spotlight on Henry Sloss, who has been steadily crafting poems for decades. His new collection, Forty Quartets (Orchises Press; purchase by contacting [email protected]), is a kind of Book of Days taking us through the seasons. Each poem is comprised of four sestets, employing enjambment, slant rhyme, and an envelope rhyme scheme of ABCCBA. He offsets this tight, if old-fashioned, structure with a natural conversational tone, as he finds himself living “what was known/once as a quiet life.”

One poem characterizes the waning of desire not as serenity so much as “a sort of nonchalance, /a shoulder-shrugging calm,” ending with a moving double entendre: “the fall’s long unfolding.”

He calls himself a codger or hermit. He is solitary and withdrawn, cognizant of time’s cyclical nature, but he also knows that time, for him, is running out. And he’s challenged by the need to fill his hours productively, in planting and watering the garden. It’s hard to plan ahead when “life can seem less/a blessing than a curse” and “all to the whirled succumb.”

His wise musings are impeccably paced even when the mood is occasionally dark. In one piece, it’s hurricane season, wet and dispiriting. Dread isn’t easily passed off as he anticipates “the accident, the awful/onset, the empty bed.”

Overall, though, there’s little self-pity. “Oh, no, don’t go there please!” he interjects. Or, “Wait! Isn’t your gardening fun and good exercise.” And elsewhere “...look! whole trees peeled/to skeletons succeed/in framing winter’s language.”

There’s weeding to be done in the garden, as in the self. And when the crops seem overly abundant, he pokes fun at himself. “The ‘Joy of Canning’ wanes, but you can’t just stop.” The seasons “step forward and step back/Seem ready and then balk.” In another poem, he finds it wearisome that tomatoes keep coming after their prime, as if they can’t wholly decide to stop. He finishes:

The other shoe will fall,

As the first fell at birth,

Beyond your yea or nay,

If life’s a holiday

From nothingness, the earth

Is heaven after all

No rage at the dying of the light in this beautifully crafted collection. Instead, a charming forbearance, a lightness of touch, and a quality we could all use more of these days: genuine humility.

Amanda Holmes Duffy is a columnist and poetry editor for the Independent and the voice of “Read Me a Poem,” a podcast of the American Scholar.