New collections to make life more lyrical.

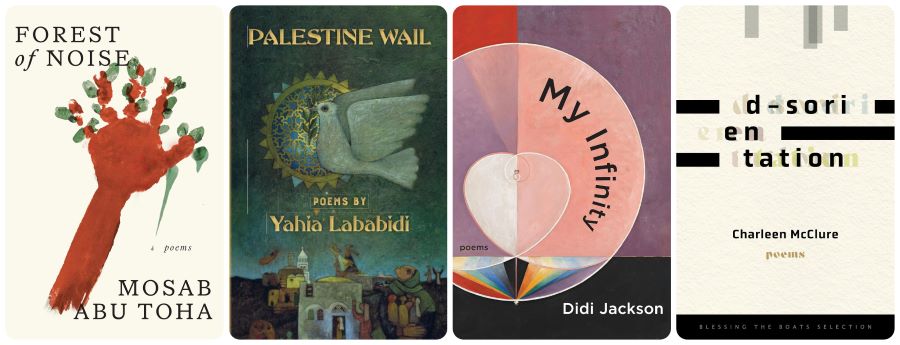

A short passage in Mosab Abu Toha’s Forest of Noise (Knopf) has haunted me for weeks. It captures home in a Palestinian village, the traces of which exist now only in memory:

On a hill in a village, you can chock

the wheels of your vegetable cart

with a stone your grandfather once used

to crush thyme. Or smash garlic with

a stone your grandmother used as a doorstop.

You can lounge

On a wicker chair near a pomegranate tree,

where a canary never tires of singing.

It’s the meager blessings that make these lines so heartrending. Audre Lourde wrote that poetry isn’t a luxury. For Abu Toha, it’s a need. He needs to document the horrors in Gaza, but horrors interspersed with recollections like this. Forest of Noise is thus both love song and eulogy.

He writes in “Obit”:

To the shadow I had left alone before I

crossed the border, my shadow that stayed

lonely and hid, in the dark of the night,

freezing where it was, never needing a visa.

To my shadow that’s been waiting for my return,

homeless except when I was walking by its side

in the summer light.

In another piece, a neighboring family loads their furniture into a truck, leaving behind the grandfather’s portrait, because “if we removed it the whole house would crumble.” In Abu Toha’s Gaza, the very ants, fish, and flies are impacted by war, and “the moon overhead/is not the moon.”

He writes in brutally stark terms of detention and torture at the Rafah border crossing. But later, in exile, he recalls his grandfather’s orange harvest, concluding:

my harvest is yet to arrive,

my seeds only sprout on this page.

It’s worth remembering that, for Abu Toha, English is a second language. There’s a lot of heavy content and trauma on the page, but Forest of Noise is a deeply resounding collection.

*****

Poetry is also song in language. And what is song if not harmony in which we might find healing? Writing from the Palestinian diaspora, Yahia Lababidi, an Egyptian American of Palestinian descent, dedicates Palestine Wail (Daraja Press) to his grandmother, Rabiha Dajani. “Forced to flee her ancestral home in Palestine at gunpoint nearly 80 years ago,” he writes, “she went on to become a remarkable educator, activist, and social worker.”

The collection’s opening section, “Unbearable Casualties,” is angry, confused, and conflicted. You feel the poet trying to write himself sane (his phrase to me in a recent communication). Perhaps some of these poems hatched a little early, but the subsequent sections, “Lingering at the Threshold” and “On a Far Shore,” are marked by spiritual and philosophical yearning. For him, during Ramadan:

To fast is to slow down

Almost to a stillness

And distill what is necessary:Sacrifice, patience, obedience

— In other words, radical gratitude.

He also reaches for wise humor in such poems as “Minister of Loneliness,” which is an actual position recently formed by the U.K. government. He writes:

Successful candidates must be virtuosos of suffering

sensitive, of course, yet impervious to lingering sadness

tirelessly capable of encouraging others despite,

at times, feeling defeated or assaulted by pointlessness

Lababidi continually endeavors to tend the light during times of darkness. To breathe in his poems is to embark on a journey from a heartfelt wail of sorrow and despair into silent prayer.

*****

In My Infinity (Red Hen Press), Didi Jackson employs a lyrical grace and intimate tone as she seeks transcendence, even while acknowledging that not all wounds may heal. She explores personal concessions as she listens for the divine in the cycles of nature great and small, from the rising moon to the bathroom spider at its web.

Our attention is drawn to the infinitesimal, to insects and tree frogs, to the broken wings of birds and butterflies, then out to the mountains of Vermont, diurnal and seasonal cycles, the turning of leaves and setting of the sun. In harmonizing with natural cycles, she rides out personal losses:

It is the darkest days

I’ve learned to praise —The calendar packages up time

The days shrink and fold away

But the heart of this collection is a series of ekphrastic poems in conversation with Swedish abstract painter Hilma af Klint (1862-1944). Hilma held that a spark of the divine resided in all creatures and that she was channeling spirit guides in her painting and automatic writing. Working with four other women — who called themselves “De Fem” (the five) — she maintained that the spirits had instructed her to paint several canvases which would hang in a spiral temple.

Jackson’s poems inspired by Hilma’s snail-shell spirals, the channeling of inner voices, and, above all, listening led me to the paintings themselves. The deeper I got, the more luminescent the writing became, a little glimpse of infinity.

*****

D-sorientation by Charleen McClure (BOA Editions) asks us to ponder how we get our bearings, both in centering ourselves and from those to whom we are connected. When you lose someone close, the lines between states and stages of consciousness seem to blur. In grief, we feel the need to hold it together — but what do we hold and how do we orient ourselves?

In “Caretaker,” a daughter feeds her dying mother, who cannot keep the food down, then eats her own meal from the same plate and tries to digest not just the meal, but the caretaking itself and the impending loss. The poem ends:

And I’ll try to — no, I will:

I’ll keep it down.

In another poem, we find the desolate line, “I huddled in the corner & that corner was my body.” And in the poem “A Study of Human Effort,” after her mother’s death:

we went to a future that would have us and slept

in the ruins we called home

There are also a few erasure poems where McClure works with pre-existing texts and strips them down to a few disparate words on a field of white paper. How, as a Black American woman, is she to make something representing herself given what’s been handed down? And having discarded what doesn’t serve, what is then revealed?

The end result of these erasures is more intellectual exercise than poem, and yet that notion of individual space — where one person leaves off and another begins — is the overarching question of D-sorientation.

In “Arrest,” McClure uses the language of Sandra Bland, who was arrested in 2015 for a traffic violation and later found dead in her jail cell. Seeing Bland’s words cut up on the page, reading them (and also, I have to say, typing them out for this review), put me directly into the moment and into the silences around it:

I’m waiting on you. This is your job. I’m waiting on you.

When’re you going to let me go

I don’t know. You seem very irritated.

I am. I really am. I feel like it’s crap for what I’m getting a ticket

For. I was getting out of your way. You were speeding up, tailing

Me. So I move over. And you stop me. So yeah, I am a little

Irritated, but that doesn’t stop you from giving me a ticket.

{inaudible} ticket.

Finally, McClure’s ekphrastic poem after Kara Walker sent me down a thoroughly engaging rabbit hole exploring that artist’s work. D-sorientation is the kind of book that pulls the rug out from underneath you, takes you on a journey beyond personal selfhood, and then throws you back into the collective to which we all belong.

Amanda Holmes Duffy is a columnist and poetry editor for the Independent and the voice of “Read Me a Poem,” a podcast of the American Scholar.