New collections to make life more lyrical.

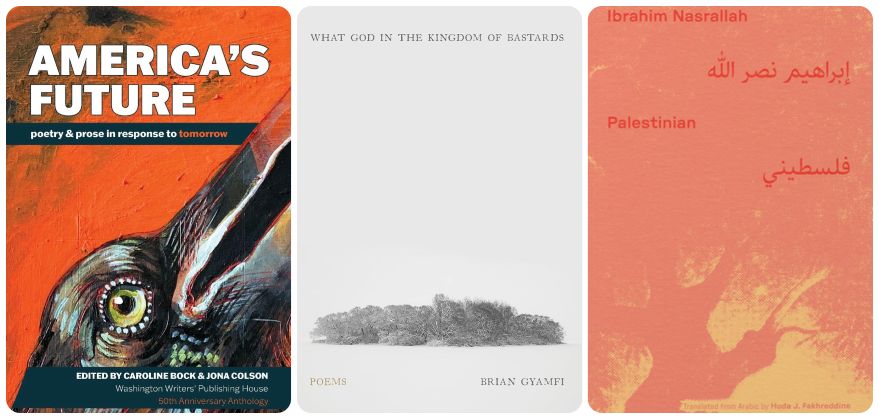

How do you feel about our country’s prospects these days? It’s a question on all our minds, and one Washington Writers’ Publishing House recently put to writers in the DMV. The result is America’s Future: Poetry & Prose in Response to Tomorrow. This anthology, showcasing the work of 164 contributors, marks the 50th anniversary of WWPH, the longest continuously running small press in the country.

But as co-editors Caroline Bock and Jona Colson write in the introduction, “...America’s Future is not just an anthology — it is a conversation with the unknown and with our community. It challenges us to confront the past, question the present, and shape the future with our art, with our words.”

Even as I write, the ground is shifting beneath our feet. Congressman Jamie Raskin’s (D-Md.) remarks at the “Hands Off” rally on the National Mall this past spring open the collection. In April, they were rousing. Today, they read like ancient history.

In the last few months, our government has become almost unrecognizable. It’s a subsequent piece by David Keplinger, entitled “American Ruins,” that feels more in line with the current mood:

Where are the American Ruins?

The guide couldn’t answer. Some-

Where here in the dry grass.

The guide kicked the grass a little.

It was a sunny day.

Mary Ann Larkin’s “Let Us Praise Sadness” invites us to unite in our despondency. It reads in part:

We will sing

Of no good news.

Nothing will be hidden,

and still we will sing,

sing of sadness,

Praise it, my friends,

and the cloud it comes from.

Such an important message of solidarity, given how many are living in fear. Doritt Carroll’s “Today,” written mostly in couplets, offers a moving prayer for invisibility, while Tony Medina’s “If I Don’t Come Home” is written in the voice of an immigrant mother whose faith in American justice has not been shaken, despite the danger of deportation.

David Ebenbach’s “Predicting the Future” contemplates the resilience and adaptability of cockroaches. “No — they’ll never outlive us,” he begins. They thrive in filth but only multiply “in the hollow of our lives.”

Another notable piece in this vein is Cherrie Woods’ “Make America Great.” Here’s an excerpt:

No more facades,

No more staged performances,

No more underserved trophies for justice

Never truly won

Perhaps America will rebuild on firmer ground. Can justice prevail in a country “built by enslaved people, for the benefit of the men who kept them enslaved” — words for a grandmother’s old DC scrapbook in Claudia Wair’s “Fireflies and Dandelion Wine”? Wair’s story imagines a futuristic “New DC,” where a guaranteed minimum income allows people to live simply, closer to nature, and spend more time on their artwork.

There’s humor and joy in these pages, too. The folksy tone of Mary Kay Zuravleff’s story “On the Hook” counters a computer-generated present and a past where everything was slave-built, with a crocheted “yarnbomb” protest made from thousands of granny squares designed to “remind you of whose hands made those bricks before their humans were sold down the river.”

I also enjoyed Jyoti Minocha’s “Wedding Plans,” a story about two mothers-in-law on opposite ends of the political spectrum that ends in joyful laughter.

Several pieces remind us about the cycles of injury and recovery. Grace Cavalieri, Maryland’s 10th poet laureate and the founder of WWPH, gives us “The Bird in the Crib,” where a wounded bird is healed and takes flight, only to return years later, “muddied and hurt, wings and legs broken/ Something we could never have prevented.” The poem ends with the sense that we can “begin again with tears that calm the dark/lifting the curtain to see the stars.”

Which brings me to Leeya Mehta’s “The Day After: Searching for Language for Another Lost Generation.” This stand-out piece is a meditation on several challenges we’ve confronted in the past and which we face again today. Her compassion and wisdom steady me, as does her plea for a softening of rhetoric.

But let me finish with “Cascadia, or a Spell to Banish the Abyss of Him Without Moving to the West Coast” by Jacob Budenz, who now goes by JB Aris. Halfway through this raw and deeply personal poem, Aris reflects that “Nothing grows/ from nothing, no forest/renews without a little ash.”

Right now, it appears that democracy is up for grabs, and who knows where we’ll be next month. But America’s Future is a heartfelt affirmation of a powerful spirit in this country. Pick up a copy at your local bookstore. Remind yourself of who we are.

*****

The first thing you notice about Brian Gyamfi’s debut collection, What God in the Kingdom of Bastards (University of Pittsburgh Press), is voice — the powerful, original voice of one who is at once disconnected from and tethered to the African culture that thrums within him. Gyamfi is a Ghanaian American whose poetry deals with Black identity and the inheritance of ancestorial trauma. Consciousness here can shift from the physical body to a felt sense outside it, into insect, dust, body of water, breeze, or trees.

I’m reminded of something Wiradjuri poet Jeanine Leane once explained to me about Australian First Nations poetry. “You have packed your wrong suitcase to come to our space if it’s packed with this Western enlightenment agenda,” she said. “You’re welcome to our stories but unpack your cultural suitcase. Let us tell you what to bring.”

As I struggled to unpack these poems, I often felt I wasn’t divesting myself quickly enough of my wrong suitcase. How to equip myself with the right one was another question! I was drawn in and then again held off, and this was surely the poet’s intention.

Gyamfi writes as one estranged from his origins — from his grandmother, for example, who doesn’t belong in the Western world, although they haunt each other. Father is disconnected from son, lovers and brothers are united in miscommunication. The new world cannot be explained to the old one.

Certain culturally specific concepts have no equivalent in other languages and therefore cannot be translated. There’s a sense of alienation in a Western classroom. The American history of racism is not entirely the speaker’s own, but somehow, he must wear and endure it.

The speaker sometimes hovers between lifetimes or is conscious of passing through them too quickly. Take, for example, “Columbarium.” Here’s an excerpt:

I had little luck or chance

to find a pen at the bar.Was dismantled into fragments

& cremated.

I promise I asked

& was denied the chance

to hold my own dustin a jar.

“The Almost Love Poem of Eloise and Kofi” is particularly affecting. Why an almost love poem? Eloise tells Kofi she wants a divorce, but he is incapable of responding, absorbed as he is in preparing her favorite food — ox tongue cooked in tomato juice. Eloise’s desire for divorce is irrelevant, as Kofi “has a chance to recover his patience and pull it over himself.” What they feel for each other is in a different register to the concepts of love poem or divorce. People whose needs are rarely prioritized don’t have words to articulate such needs. The poem ends:

Love is a wretched,

Wretched thing. Eloise wishes Kofi would put down

the tongue and say something.

Food preparation can be a language of love as well as a means of rejecting it. In “Age of Nudes,” the speaker asks his lover, “how do people find their way to each other?” “With sweets and nakedness, she says.”

But in “Horseradish,” relatives sit together on a couch, where “there’s repressed violence,” while, in the background, Kwame cooks a special rice dish that one of them will refuse to eat. When the speaker retells this story to his lover, what transpired is lost. She asks to hear the story “about cooking,” but, of course, it isn’t about cooking at all. They want to connect but “both know there is brokenness in our bodies.”

I haven’t done full justice to Gyamfi’s collection here, but I hope I’ve piqued your curiosity. What God in the Kingdom of Bastards is a multifaceted, multilayered debut to put at the top of your reading list.

*****

Palestinian poet Ibrahim Nasrallah is the author of 24 novels and 14 collections of poetry. Palestinian (World Poetry) is a chapbook in Arabic with beautiful English translations by Huda J. Fakhreddine on facing pages. The poems come out of the current crisis in Gaza.

All four poems collected here have the quality of prayers and laments, with the first sounding a drumbeat of despair with the repeated refrain, “nothing came of it.” The poem begins:

I was silent and nothing came of it.

I spoke and nothing came of it.

I cursed, I apologized, and nothing came of it.

I was busy, I pretended to be busy...and nothing.

In a sense, the poem takes us through Palestine’s history of desperation and hopelessness. This is particularly poignant today as the people in Gaza are quite literally being cornered and pushed into ever-shrinking “safe havens,” with no escape or guarantee of safety.

At this writing, more than 20,000 children have been killed in Gaza, and not just by airstrikes and drone attacks. Now, they are dying of starvation. “One Hundred Questions and More: A Child in Gaza Asks You” is a three-and-a-half-page poem of heartbreaking questions about the world beyond Gaza. It’s the simplicity of the questions that makes this poem so devastating.

The final poem, “Mary of Gaza,” asks us to consider the concept of peace. Are there any people who do not deserve it? Is peace for tyrants and oppressors? This is a world turned upside-down. The echoing refrain here is “peace on earth is not for us.” How can this be, we ask ourselves, and yet what else can we conclude? Read an excerpt:

Peace on earth is not for us.

It is for our enemies, It is

For their planes. It is for death as it descends

And death as it ascends

For death as it speaks, lies, and dances.

Nothing satisfies it,

Neither our blood in sorrow nor our blood in beauty,

Neither our blood in the seas, nor our blood in the fields.

But in the final stanza, Nasrallah turns this around, writing:

I will not say: Peace is for those who kill, uproot, and burn,

Peace on this earth was ours before them here,

And peace on this earth will be ours after them,Peace is ours. Peace is ours.

The eyes of the world are fixed on Gaza now as never before, an irony to be grateful for. In Nasrallah’s interview with his English translator at the end of the book, he says, “Today, Gaza, that small strip of land, is as large as the world, and its struggle for survival is one of the projects to liberate the world from darkness and tyranny.”

We’ve watched the live-streamed genocide, but journalism cannot do the profound empathetic work of poetry. Through poetry, we synchronize with the rhythms and cadences of others. When we read poems like these, especially aloud to ourselves or for others, something happens to us physiologically. We unite in the frequency of the poem, connecting with the poet on a deep level. And what we feel alters our mental atmosphere.

Now more than ever, this is what’s needed to turn things around. In reading books such as this one, Fady Joudah’s [...], or Mosab Abu Toha’s Forest of Noise, we open our hearts to the Palestinian people. We reject silence and enter our collective protest against human suffering.

Additionally, a percentage of the proceeds of the sale of this book will go toward KinderUSA, whose stated mission is “to improve the lives of Palestinian children and other children in crisis through development and emergency relief.”

Amanda Holmes Duffy is a columnist and poetry editor for the Independent and the voice of “Read Me a Poem,” a podcast of the American Scholar.