Novelists draw from history’s myriad injustices to great effect.

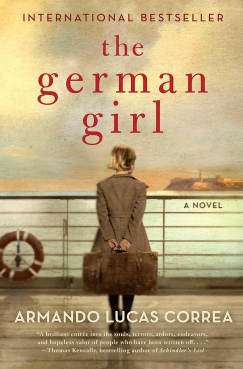

When I went recently to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and saw its account of the voyage of the St. Louis, it made me think of The German Girl, a novel by Armando Lucas Correa. The book, which sat on my shelf for quite a while before I read it, recounts the story of Hannah Rosenthal, who fled Nazi Germany with her family in 1939 on the ill-fated ship, which had promised Jews safe passage to Cuba.

The novel alternates her story with that of her grandniece, Anna, whose father, the son of Hannah’s estranged brother, was killed at the World Trade Center on 9/11. Hannah’s story in Havana, where she was one of only 28 people allowed to land, progresses through the Castro revolution and up to the point where Hannah meets Anna.

The chilling real-life aspect of the story is how more than 900 passengers on the St. Louis were not permitted to stay in Havana and were subsequently turned away from the United States and Canada, too, ultimately finding refuge in Britain, Belgium, the Netherlands, and France. Tragically, many ended up in concentration camps.

The Nazi death camps, where Hannah’s father perished, are graphically portrayed in the streaming series “The Tattooist of Auschwitz,” based on the book of the same name by Heather Morris. The novel and the series get some historical details wrong, but the touching tale of Lali Solokov and Gita Furman shows how love can survive even unspeakable horror.

I grew up in St. Louis and spent some 11 years in Germany working as a journalist. While a student in Munich, I met Holocaust survivors with tattooed numbers on their arms. I lived for a while in Hamburg, where Hannah and her family boarded the Hamburg-Amerika Line ship, and covered the Hapag-Lloyd company it eventually became. The German Girl was, in short, a story that resonated with me.

I also just visited the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, which features an account of slave ships — like those portrayed in Charles Johnson’s Middle Passage — and traces the history of race relations in America.

My wife, Andrea, then put me onto James, the newest offering from Percival Everett, whose 2001 novel Erasure was the basis for last year’s marvelous film “American Fiction.”

James tells the story of Huckleberry Finn from the POV of the enslaved Jim, who accompanies Huck on the raft down the Mississippi. It includes details of the pitiable plight of the enslaved as portrayed in “12 Years a Slave,” the 2013 movie starring Chiwetel Ejiofor and based on the memoir of the same name by Solomon Northup, a free Black man who was abducted and sold into bondage.

Everett’s latest plays on the same theme as Erasure — how language is used to keep Black Americans in their place. Jim’s pidgin English is a cover for his ability to speak conventionally and to read; it’s a way to fool “white folks” and maintain his position in the order of things.

James has already been hailed as a masterpiece — and is longlisted for the 2024 Booker Prize — and Steven Spielberg has signed on to make it into a film. But don’t wait for the movie. The book is great.

Darrell Delamaide is a journalist and writer in Washington, DC.