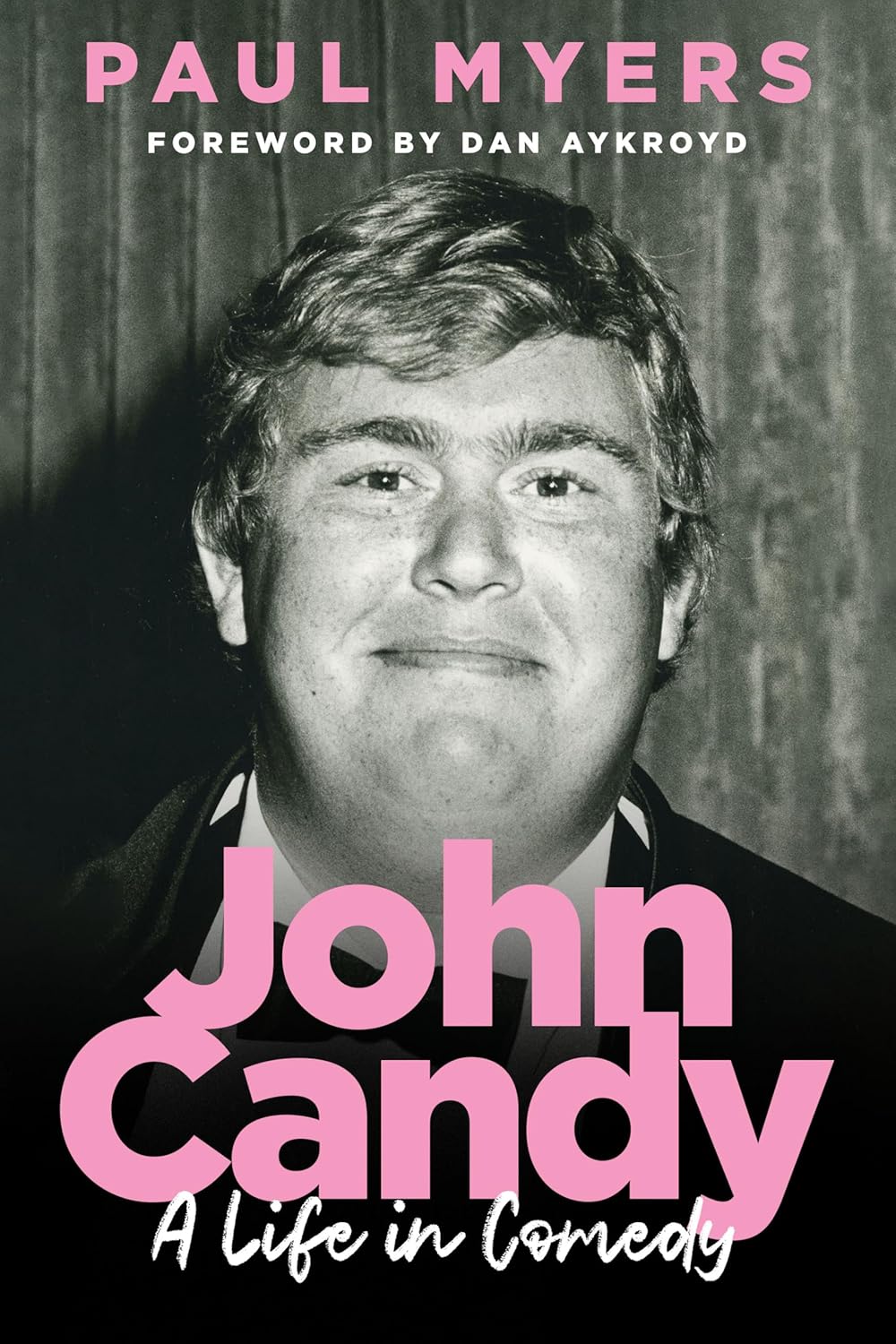

John Candy: A Life in Comedy

- By Paul Myers

- House of Anansi Press

- 376 pp.

- Reviewed by Daniel de Visé

- October 21, 2025

An affectionate, uncritical look at the beloved comic’s career.

Who was the greatest alum of Second City, the famed improv troupe, to never perform in the cast of “Saturday Night Live”? If you made a top-10 list, it would probably include John Candy, the subject of a new biography, John Candy: A Life in Comedy. Paul Myers, the author, is the brother of Mike Myers, one of the greatest Second City alumni who did join the cast of SNL.

That pedigree both helps and hurts this bio. Myers gained access to many great artists who knew and loved Candy, including Dan Aykroyd, Chevy Chase, Tom Hanks, Ron Howard, Steve Martin, and Catherine O’Hara. That is an amazing feat: I write books, too, and I tried and failed to interview a few of those same stars for my own past projects.

I would gently chide Myers, though, for not pushing his celebrity interviewees harder. Most of what they say in John Candy is celebratory. Little is revelatory. I sense that Myers himself is too close to the industry to quote famous people saying things that might land them in trouble.

That said, John Candy does an estimable job of narrating the great comedic actor’s life and of explaining what made him tick. Myers is a good writer, and he knows his material.

Second City, as any SNL fan should know, arose from the University of Chicago theater scene in the 1950s and more or less singlehandedly spawned the golden age of improv in America.

Candy grew up in Toronto. His father died when John was 4, a tragedy that would haunt him for the rest of his own abbreviated life. In 1973, he auditioned for a satellite Second City troupe that was opening in Toronto. He landed a spot not in Toronto, but at the mothership in Chicago. He eventually returned to Canada to join perhaps the greatest Second City cast ever assembled, one that included Aykroyd, Eugene Levy, and Gilda Radner.

In 1975, Lorne Michaels raided Second City (and “National Lampoon” in New York) to empanel a cast for his new late-night show, “Saturday Night.” Radner and Aykroyd went to SNL. Candy and Levy did not, and they eventually joined a rival program launched by Second City.

“Second City TV” was arguably better than SNL, at least in terms of week-to-week consistency. Between 1976 and 1984, its stellar cast included Candy and Levy, O’Hara, Joe Flaherty, Rick Moranis, Martin Short, Andrea Martin, Harold Ramis, and Dave Thomas. The program mercilessly parodied Hollywood blockbusters (“Chariots of Eggs”), network sleaze (“Battle of the PBS Stars”), soap operas (“The Days of the Week”), and UHF cheese (“Monster Chiller Horror Theatre.”) No one could top Moranis’ Woody Allen impression, but Candy was the program’s real standout.

Hollywood gradually recognized Candy’s star power. He was a big, lovable teddy bear, fiendishly funny but in an everyman way, much like Aykroyd and Belushi, who invited him to play a small but memorable role in their 1980 classic, “The Blues Brothers.”

Candy logged strong performances alongside Bill Murray in “Stripes” (1981), Chase in “Vacation” (1983), and Hanks in “Splash” (1984). He ascended to top billing in the solid 1985 comedy “Summer Rental.”

Over the next several years, Candy would star in several good films, including Mel Brooks’ “Spaceballs” (1987), Howard Deutch’s “The Great Outdoors” (1988), and Chris Columbus’ “Only the Lonely” (1991). He did his best film work for John Hughes, who directed him in the very good “Uncle Buck” (1989) and the extraordinary “Planes, Trains and Automobiles” (1987). That last picture, opposite Steve Martin, was Candy’s one great film.

Had I written a John Candy biography, I probably would’ve devoted several chapters to “Planes, Trains and Automobiles,” and several more to Candy’s stellar work with SCTV. I might’ve spent a page or two, at most, on the other films.

Yet Myers politely parcels out full chapters on several of Candy’s lesser projects, a gesture that serves the historical record but saps the book of energy. There’s also a long narrative on Candy’s ownership stake in a Canadian football team that will mystify most U.S. readers.

Still, along the way, Myers captures many poignant observations about Candy from his famous friends. He had great ideas but lacked the patience to write them down, a trait he shared with Belushi. He could joke about his own weight problem, but heaven help the screenwriter or director who dropped fat jokes into his scripts. (The mud-wrestling scene from “Stripes” was particularly painful for him.) And Candy apparently passed on a role in “Pulp Fiction,” one of the greatest films ever made.

We also learn that Candy had a kind of death wish. His father had died young, after all, and Candy felt he was living on borrowed time. He ate and drank too much. He slept too little.

“You had the feeling he was on a spiral,” Steve Martin told Myers, in one of the few celebrity quotes that portrays the complicated Candy as more than a jolly good fellow.

Candy died of a heart attack in 1994, at 43, while filming a dreadful movie in Mexico. Maybe he had more great films in him. Maybe not. We’ll never know.

“There’s a word in our language we don’t hear much anymore,” Aykroyd said in a stirring eulogy, “but it applies to Candy. The word is grand. He was a grand man.”

Daniel de Visé is the author of five books, including The Blues Brothers: An Epic Friendship, the Rise of Improv, and the Making of an American Film Classic.