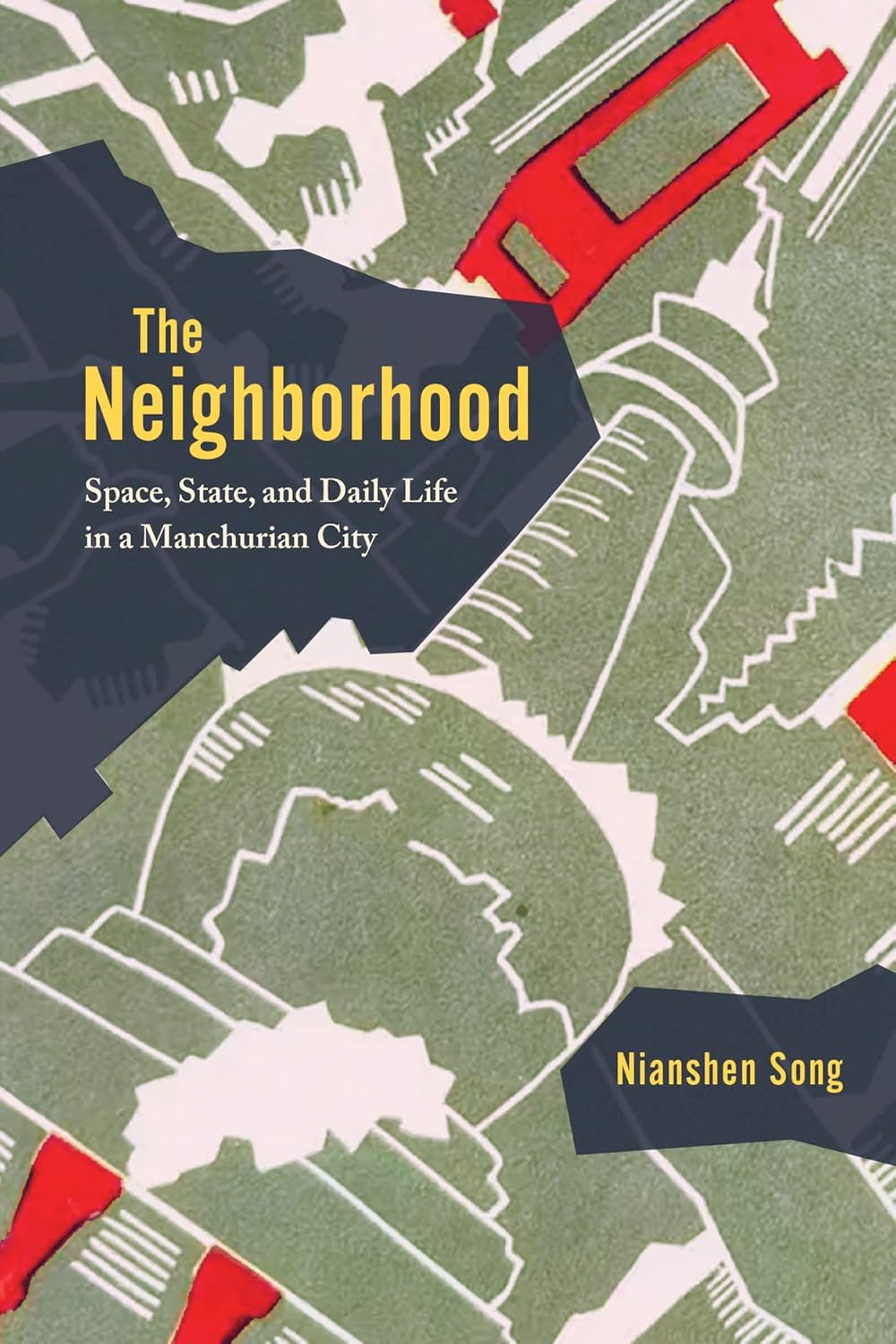

The Neighborhood: Space, State, and Daily Life in a Manchurian City

- By Nianshen Song

- University of Chicago Press

- 304 pp.

- Reviewed by Eileen Miller

- February 19, 2026

An unremarkable Chinese crossroads proves anything but.

Few authors would make the choice to disparage the subject of their book in its opening pages, but in declaring the neighborhood of Xita, “a place of little significance” in the introduction of The Neighborhood: Space, State, and Daily Life in a Manchurian City, Nianshen Song does just that. This is not the declaration of a scholar frustrated by years of wasted fieldwork, however, but rather a point critical to the central theme of the work.

The neighborhood in question is Xita (written as 西塔 in Chinese and pronounced “she-ta”), located in Shenyang, capital of the northeast Chinese province of Liaoning. It is of such minor significance, Song notes in his epilogue, that even some of Shenyang’s residents have little impression of it.

Yet through close analysis of a diverse array of primary sources, he recounts the surprisingly numerous instances in which the broader history of East Asia came through this neighborhood and profoundly shaped its development. Though seemingly inconsequential, Xita — covering just half a square mile — doubles as an unlikely mirror of China’s own transformation over three-and-a-half centuries.

The Neighborhood begins with the convergence of religion, politics, and ethnicity. In 1644, to enhance their connection to the Mongol-majority Inner Asia territories, the Qing emperor strategically chose to patronize Tibetan Buddhism, the dominant religion of the Mongols. From this alliance, Xita got its name, a reference to the West Stupa, a mound-like tower built on the site of a Buddhist temple on the outskirts of what is today Shenyang. From here, Song delves into the priest-patron relationship between the Qing state and the Tibetan Buddhist lamas and how this unique relationship influenced the lamas’ daily lives.

With the fall of the Qing Dynasty and transition into the Republican Period, the alliance between the Qing and the Tibetan Buddhists unraveled, and the population of latter in the region declined. Through these developments, Song strengthens his case for Xita’s mirroring of Chinese history writ large.

As this history moves forward, Song keeps his focus anchored on the West Stupa temple. The next period was profoundly shaped by Japanese imperialism, and Xita was no exception, experiencing the turmoil of imperial competition through the rival Russian, Japanese, and Chinese railroads that cut through it. After a train station was built near the West Stupa, the neighborhood underwent urban development and witnessed an influx of Japanese tourism. As the Japanese Empire sought to justify its role as the dominant power in Asia, it turned to the neighborhood’s Tibetan Buddhist roots — and symbols of that identity like the West Stupa — to tie Japan to the rest of Asia and promote the imperial narrative of a pan-Asian network led by Japan.

In later chapters, Song’s retelling of history remains rooted in Xita and the West Stupa temple, revealing just how many of the developments of contemporary Chinese history echoed in this small neighborhood. His recounting of Xita’s transformation into an ethnic Korean enclave reflected the wider history of the Korean diaspora in East Asia, as well as the ups and downs of China’s economic transition. He enriches his historiography with interviews from several ethnic Korean residents of Xita, showing how the past shaped not just the neighborhood but the daily lives of its inhabitants.

As the neighborhood took on various roles and identities — serving as a symbol for the ties between Tibetan Buddhism and the Qing government; site of imperialist competition; home for ethnic Koreans in an era of turbulence; thriving commercial center in a rust-belt town; a model for multiethnic harmony — so did East Asia and China undergo these changes.

Meticulously researched, The Neighborhood draws upon a rich array of sources to provide a roving picture of a place across 350 years. Its impressive bibliography includes, among other things, résumés of Buddhist lamas, 20th-century travel guides, travelogues by Japanese writers, postcard images of the West Stupa across time, and firsthand interviews with ethnic Korean residents. This combination of sources allows Song to keep his focus tethered to Xita while exploring the city through various lenses, from religion, imperialism, and tourism to commerce and migration.

The Neighborhood is remarkable for its sustained focus on a single small place, just as Xita and the West Stupa for which it was named are remarkable for the layers of history that cross through them. Though Xita is unlikely to be mentioned in many contemporary travel guides, Song’s book successfully makes the case for dedicating academic attention to this “place of little significance,” and maybe taking a trip there, too.

[Editor’s note: This article was written with support from the DC Arts Writing Fellowship, a project of the nonprofit Day Eight.]

Eileen Miller is a DC Arts Journalism Fellow with Day Eight. She currently lives in Washington, DC, where she is pursuing a degree in East Asian studies at Georgetown University. Her writing has also appeared in DC Theater Arts and the Georgetown Voice.