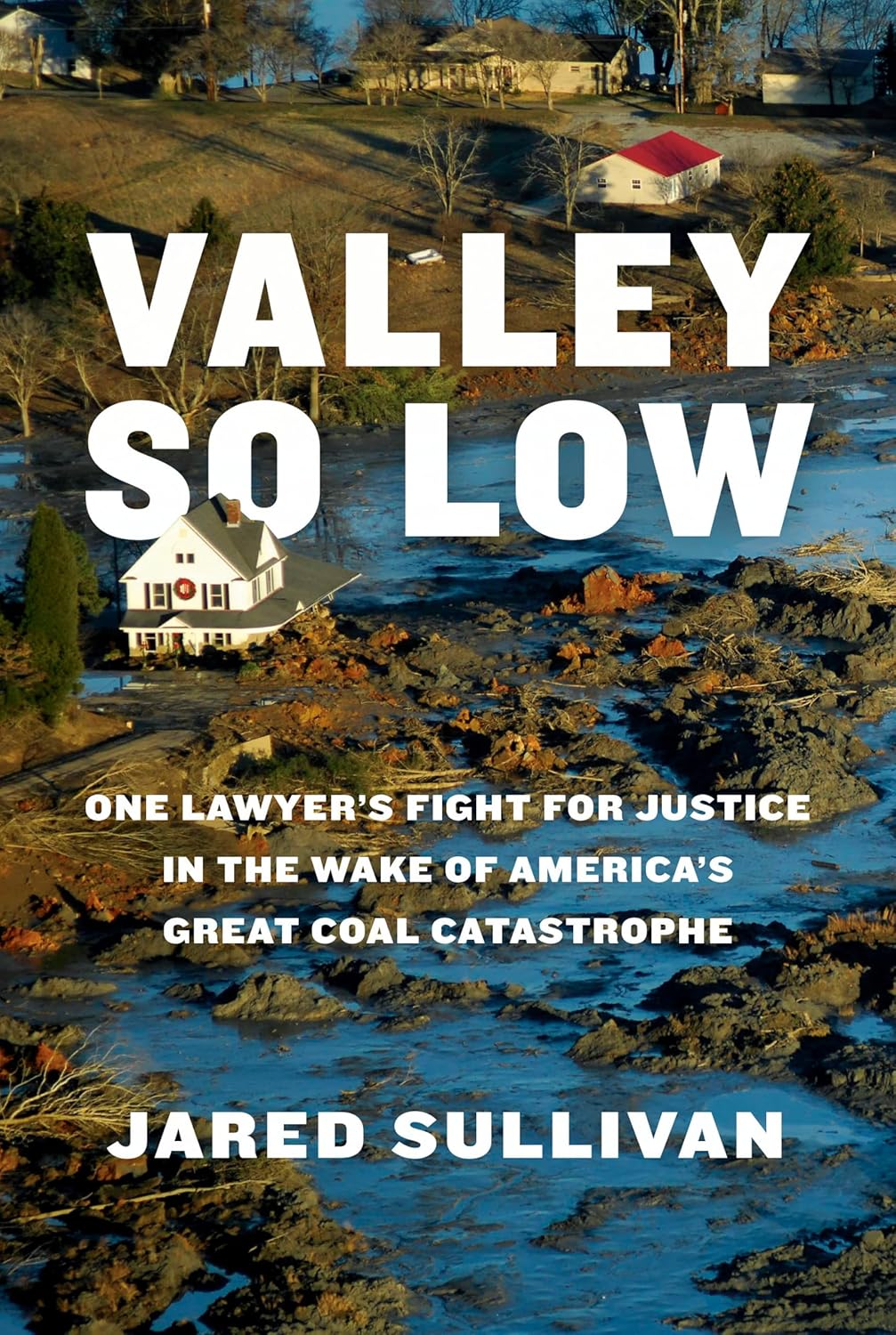

Valley So Low: One Lawyer’s Fight For Justice in the Wake of America’s Great Coal Catastrophe

- By Jared Sullivan

- Knopf

- 384 pp.

- Reviewed by Larry Matthews

- November 7, 2024

How a small-town attorney gave injured workers their day in court.

In the early morning hours of December 22, 2008, as Christmas lights sparkled in homes in East Tennessee, an environmental catastrophe swept a wide area of Roane County, not far from the city of Knoxville. It happened at the Kingston Fossil Plant, a federally owned power company managed by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). The plant provided electricity to hundreds of thousands of homes across the South. It burned 14,000 tons of coal a day, producing 1,000 daily tons of coal ash in the process.

In the 1950s, the TVA began storing the ash in a spring-fed swimming hole. In the following years, it grew into a 60-foot mountain that covered 84 acres at the confluence of the Emory and Clinch rivers. The dike holding back the ash wasn’t concrete, it was dirt. Not long after midnight on December 22nd, it gave way. More than a billion gallons of coal-ash slurry broke free, producing a wave 50 feet high. It filled the Emory, tossing fish 40 feet onto the riverbank. It crushed trees and smothered roads and everything else in its path, including homes. The toxic stew killed people and animals and ruined the landscape.

Jared Sullivan’s Valley So Low tells the story of what happened next.

The TVA was started under President Franklin D. Roosevelt during the Great Depression. It had two purposes: electrify the South and create thousands of jobs in the process. In its early years, the TVA dammed rivers in East Tennessee to generate electricity. Later, it built coal-fired plants, including the one in Kingston. The federal government didn’t provide much oversight, and safety and health matters weren’t addressed in a serious way.

I have a personal connection to all of this. My father’s family is from East Tennessee. An uncle worked at the Kingston plant for years, often complaining about the dust and the contaminated water. As a boy, I fished in those rivers and ran with my cousins in the hills. One of those cousins would become the sheriff of Roane County, where the disaster occurred.

He took me on tours to point out the noxious ground and water, a condition made worse by Oak Ridge National Laboratory, also in Roane County, where America produces its nuclear weapons, seeding the land with radiation, mercury, and a long list of other extremely dangerous materials. My cousin couldn’t understand why some of that land was being used to build retirement homes for Yankees — folks who probably had no idea what was in the earth beneath them.

The Kingston plant disaster was just one more outrage in what early European settlers believed was paradise: the Tennessee Valley, once teeming with wildlife, fish, and lush, beautiful hills at the base of the Great Smoky Mountains. Now, the water was black, the air was choked with toxic dust, and the TVA was trying to manage a public-relations nightmare.

The central character in Valley So Low is a local lawyer named Jim Scott, who took on the TVA on behalf of the spill’s cleanup workers in a legal war that spanned years, cost him his marriage and his health, and made him a kind of hero to those who suffered the gravest effects of the calamity.

Sullivan has done an outstanding job of taking us into the lives of Scott and others as they grappled with the lethal fallout from the poisoned environment and the TVA’s efforts to cover it all up. Because the TVA insisted coal ash is harmless — and its corporate lawyers didn’t want the public surmising otherwise — it forbade workers from Jacobs Engineering (the primary cleanup company) and elsewhere to wear masks onsite. Those who were sickened and ordered by their doctors to do so anyway were fired. Some later died.

Clearly, the ash wasn’t just harmful, it was deadly, something verified in an internal Jacobs Engineering document discovered by Scott. “One of the subsections included a table, and this table listed six toxic constituents of fly ash,” writes Sullivan. “Among them: arsenic, aluminum oxide, iron oxide and silica — a Long Island ice tea of poison.”

The report went on to say that “fly ash’s constituents could harm the eyes, liver, lungs, kidneys, and respiratory system…Elsewhere, the document stated that the Kingston fly ash contained selenium, cadmium, boron, thallium, and other metals,” some of them radioactive.

It was found that sediment at the bottom of the Clinch and Emory rivers also contained large quantities of radioactive waste and that disturbing it — which the coal-ash disaster dramatically did — would pose a serious threat to the public and to the people tasked with cleaning up the mess.

The legal wrangling lasted until January of 2023. By then, dozens of the cleanup workers had already died, others were very sick, and many lives had been ruined. In the end, thanks to Scott’s dogged efforts, the nearly two-dozen workers left in the fight received compensation amounting to $220,000 each.

Politicians made speeches promising that such an event would never happen again. A few laws were changed. But parts of East Tennessee remain a poisonous, radioactive soup. Paradise lost.

Larry Matthews is the author of the Dave Haggard thrillers.