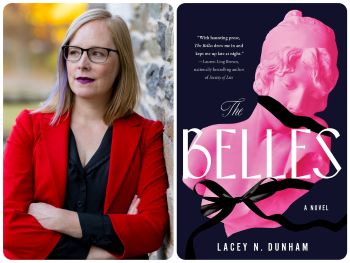

The novelist leans into the gothic in her dark-academia debut.

Lacey N. Dunham’s debut novel, The Belles, casts a light on the chilling underbelly of adolescence. Set in early 1950s Virginia, the story follows 17-year-old outsider Deena Williams as she enters her first year at genteel Bellerton College. Concealing her lower-class background in order to fit in, Deena clings to five other girls in her dormitory. After they’re anointed “The Belles” by the college president’s wife, the teens test the boundaries of their power and influence as sinister happenings from the school’s past resurface in unavoidable ways.

What inspired you to write a Southern gothic, dark-academia story?

I knew from the start I wanted to write a gothic novel and include spooky or possibly supernatural elements. I love gothic literature past and present, and it’s a tradition with such a rich history that has spawned many other genres. Horror, science fiction, and suspense can all trace their roots back to 18th- and 19th-century gothic novels. Once the gothic was in place, and with the campus setting, dark academia came naturally.

The missing girls of Bellerton set the stage for what’s to come and tie together the past, present, and future timelines. Did you always envision writing from different points in time?

I always knew I would write in multiple time periods, but it took a while to settle into the final structure, with the book set mostly in the 1951-52 academic year, [with] fast-forwards into the present and a handful of scenes set in the 19th century, around the time of the college’s founding. In the end, layering the stories of Bellerton across centuries and decades via students in different eras served the story well. After all, the gothic is about an obsession with the past, and we’re all someone’s past, no matter where we are in our present.

When Deena gets the opportunity to attend Bellerton and transcend her class, at least outwardly, the reader is privy to her judgmental thoughts on the working class — she even goes as far as throwing rocks at Alice, one of the Black cleaning women. While this behavior is expected from the wealthy girls, why was it important that we get this glimpse of Deena?

It felt important for me to show Deena (and the other girls) as both victims and perpetrators of violence. Poverty is an enormous violence that we allow to happen, and one that harms people in all kinds of ways. And while Deena is learning how to pass as wealthier than her working-class upbringing, she’s largely able to do so because she’s white. It felt important to acknowledge the dynamics of both class and race in Deena’s story, especially because of the Southern setting and 1950s time period. Racially segregated colleges were still mandated by law at this point. It would have made a dishonest story to pretend Deena wasn’t affected by the social realities of her time. At the same time, I wanted the Black characters to have agency, too. Alice calling Deena out for her privilege after Deena violates Alice’s and her community’s space is one way that happens.

You write about the “black ribbon road” that keeps the girls looped inside campus, and the ribbons that the Belles wear to signify their status. But both also convey the ways in which the girls are constricted. How did you come up with this imagery, and what does it mean to you?

I graduated from an all-women’s college in Virginia that loosely inspired the school in my novel. Like Deena, I was a first-generation college student. Like Deena, my grandmother was a housekeeper, and the rest of my family were farmers or worked on the line at the auto plant. And I remember attending classes with women who wore high ponytails cinched with long ribbons and pearl earrings and pearl necklaces — even at 8 a.m. classes! The ribbons have stuck with me, so it seemed inevitable that they would end up in my novel. And now ribbons are back with things like coquette fashion and the tradwife hairbow. Ribbons don’t scare me necessarily, but tradwives do.

Girlhood is at the core of this story. So is feminine rage. Were these themes at the forefront of your mind while writing?

Feminine rage definitely was something I thought a lot about while writing the novel — specifically, the ways women are taught to subsume their own anger or to be called to account and apologize for an outburst or for raising their voice or for “making a scene.” And how women’s anger, especially in the dominant culture, is taboo. I return often to an essay by novelist Lynn Steger Strong called “Why I Wanted to Write About Anger” to help me think through these ideas. Soraya Chemaly’s book Rage Becomes Her is another great one that I read and reread in the couple of years leading up to when I wrote the novel.

Ada May Delacourt, tacit leader of the Belles and a descendant of the school’s founder, is an interesting linchpin. Her lineage is from a woman who is described as a devil, and Ada May is protective of her talismanic emerald ring, passed down through the generations. There seems to be a dark spirituality underlying the book. Can you speak on that?

Gothic novels traditionally are also very interested in questions of lineage and power, and I wanted Ada May to believe that she’s both guided and protected by her ancestors, and the ring was a concrete way to put that on the page. She’s confident that because of who she is, she’s untouchable. No matter what lines are crossed, she’ll remain unscathed because of her lineage. As to the question of where that power comes from — I’ll leave that up to the reader to decide.

[Photo by Carletta Girma.]

Shelby Newsome is a writer and bookseller living in Maryland. Her fiction has appeared in Rose Books Reader and Black Warrior Review’s Boyfriend Village, among other outlets.