The military expert shares the story of unsung Vietnam War hero Doug Hegdahl.

On the night of April 6, 1967, U.S. Navy Seaman Apprentice Doug Hegdahl, 20, found himself swimming for hours in the Gulf of Tonkin after falling from his ship, which was under fire off the Vietnamese coast. Once captured, he spent more than two years in the “Hanoi Hilton” as the youngest, lowest-ranking prisoner-of-war ever to be held in the infamous facility.

During his time in captivity, Hegdahl pretended to be the “incredibly stupid one” while surreptitiously memorizing the names, ranks, and service branches of his 254 fellow inmates. Once released, Hegdahl brought that treasure trove of information — including previously unknown details of torture by the North Vietnamese — first to the Pentagon and then to the public.

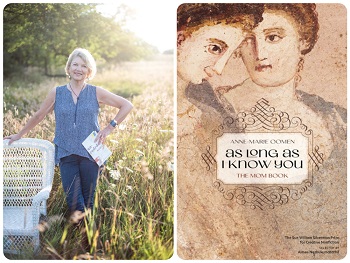

Marc Leepson’s The Unlikely War Hero: A Vietnam War POW’s Story of Courage and Resilience in the Hanoi Hilton tells Hegdahl’s story fully for the first time. Leepson, himself a Vietnam vet, points out that, to this day, the Pentagon has never officially recognized Hegdahl’s heroism. The author of 10 books and a contributor to such outlets as the New York Times and Smithsonian, Leepson is also a senior writer and columnist for the VVA Veteran, the magazine of the Vietnam Veterans of America.

With so many memoirs and books about Vietnam POWs, why did you think Doug Hegdahl’s story needed to be told?

I really, really believe Doug Hegdahl did something heroic…Doug figured out this ploy after capture and pretends he’s just this dumb hick. He does this for two-and-a-half years while learning the tap code, the sweeping code, to communicate with other prisoners. On his release, he never said he was a war criminal. And…[he memorized] the names of 254 other POWs. After he was debriefed, the Defense Department officially changed 63 guys from missing in action to prisoner. Sixty-three families learned that their father, son, [or] brother was alive.

Did Hegdahl speak to you?

Doug hasn’t spoken to anybody publicly in 25 years about his POW experience.

So how were you able to pull together his story?

Heath Hardage Lee [author of The League of Wives: The Untold Story of the Women Who Took on the U.S. Government to Bring Their Husbands Home] asked a number of her contacts if they had spoken to Doug recently. None had, and they all love Doug. She gave me Pat Stratton, son of Richard Stratton, a cellmate of Hegdahl’s. I told them what I wanted to do. They contacted Doug, who said no to being interviewed, but he did tell Dick to cooperate. We corresponded by email. Day or night, within hours, he would send long replies and suggestions. He helped me contact [Hegdahl’s former cellmate] Joe Crecca, [who] was the other guy who helped with the names. I really couldn’t have done it without them.

How do you explain the relationship as cellmates between Hegdahl, a lowly enlisted seaman, and Dick Stratton, a Navy lieutenant commander? The differences in age and status were dramatic.

As unlikely as it was, Dick Stratton felt a bond with this kid. He’s the one who encouraged him to memorize the names.

Although there was no formal chain of command as POWs, didn’t Stratton “order” Hegdahl to take an early release to get the names out and tell the story of torture and of the prison conditions?

Stratton said even though Doug disobeyed a “direct order,” he admired him for it. Then the situation changed a year and a half later. Doug knew it was time [to accept early release].

What were the attitudes of POWs to those who took early release?

The overwhelming majority have nothing good to say about them.

Was Hegdahl an exception?

I downloaded all the oral histories of POWs at the Air Force Academy. There were 12 early releasees. They didn’t have anything good to say about 11 of them. Even the fiercest resisters had nothing but good things to say about Doug. Why? Because he was the only one ordered to go.

Did the Nixon administration’s “Go Public” campaign about POWs’ treatment improve their living conditions after Hegdahl’s debriefing?

“Go Public” put pressure on the North Vietnamese to be more forthcoming.

And didn’t Ho Chi Minh’s death in the fall of 1969 significantly change the POWs’ treatment?

Within two months, the North Vietnamese under Le Duan really dialed down the mistreatment. Torture did not stop, but it really was curtailed. They fed them more. They gave them more cigarettes. Until then, [POWs] couldn’t communicate with anyone other than cellmates. If they did, solitary. Now, they put them in groups of four, five, or six. I don’t think that was a coincidence.

You distinguish between physical stress (e.g., beatings or prolonged standing) and psychological torture. Doug brought back stories of both.

I remember there are still people way out on the left who deny that there was torture. I’ve read a dozen or more memoirs, and they mention it repeatedly. I approached the torture question like I approach anything. Gather the evidence, weigh the evidence if you determine it’s good, [and] footnote it. The Vietnamese had a pattern to their interrogations, starting with a place called “New Guy Village.” If they didn’t cooperate, most were tortured: making them stand for 48 hours, putting them in a room with one light bulb, have a guard come in every 15 minutes and not let them sleep. It’s psychological and physical.

What more would you like to know about Hegdahl?

The $64,000 question: How did he fall off the ship? He claims he doesn’t remember [and] has stuck to that story. I talked to 17 sailors from [his ship], the guided-missile cruiser Canberra. No one saw it. The scuttlebutt: [He] was pushed, got into a fight, fell, was drunk, or he was a spy.

In his teens, he was so outgoing, and now he’s almost a recluse.

I think you [have to] have post-traumatic stress after coming back from something like that. He doesn’t return calls [even to friends] half the time.

Did Hegdahl ever receive a commendation for what he did?

[The Pentagon] gave virtually every POW a Silver Star. But Doug, nothing. I really believe [his] was one of the most heroic acts outside of combat in the Vietnam War, and there are medals for that.

[Editor’s note: Richard Stratton, mentioned in this interview, passed away in January.]

John Grady, a managing editor of Navy Times for more than eight years and retired communications director of the Association of the United States Army after 17 years, is the author of Matthew Fontaine Maury: Father of Oceanography, which was nominated for the Library of Virginia’s 2016 nonfiction award. He also has contributed to the New York Times “Disunion” series and the Civil War Monitor, Civil War Navy, Sea History, Northern Mariner, and Naval History. He continues writing on national security and defense, primarily for USNI News, the online news service of the United States Naval Institute.