A Florida student reckons with what happened to her library.

The adults are at it again: arguing while the kids look on.

There is still peace in our communities, in some places, in some instances. But in other places — those in which the grownups have drawn the lines, are knuckling down, standing toe to toe, gritting our teeth, squaring off, clenching our fists — we act like dysfunctional families.

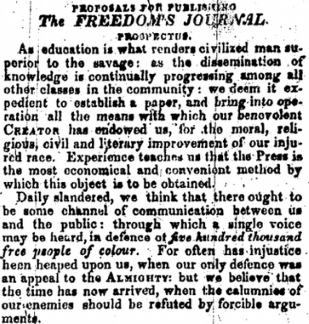

Take the dysfunctional family of Ron DeSantis’ Florida, for instance. Consider the conflict of book banning. In one school district alone, apparatchiks of the state’s censors culled 1,600 books from the shelves, saying, “They have not been banned or removed from the school district; rather, they have simply been pulled for further review to ensure compliance with the new legislation.”

Others pointed out that, whatever you want to call it, the removal of books — mostly on gender, sexuality, or anything racialized — “violate[s] [Floridians’] rights to free speech and equal protection under the law.” These folks are suing.

Sometimes, the censors double down; other times, they extend their efforts. Occasionally, the censors get in trouble and have to cave on their extreme actions. But not without first lobbing insults. Blah blah blah blah blah blah liberals blah blah blah, family patriarch DeSantis says. His press releases read like he’s standing at the head of the dining room table and banging his fists on the wood. Now he’s storming into the kitchen! Now he’s towering above the others in the living room!

Not everybody is cowering, though. There are more lawsuits. There is more fighting. It’s loud and public and highly polarizing.

The children are watching and listening. This, after all, is their world. One might wonder what it feels like to be a young person in this dysfunctional home. One of my first-year college students tells me.

When we meet over Zoom to discuss it, she recalls the day that she and her friends watched their librarians and administrators hauling books out of the library at their Florida public magnet school for the arts. “They didn’t seem happy about it,” she says of the educators forced into this anti-education role.

And she herself was frustrated. “Students were confused about what was going on. I don’t think anyone knew what was going on,” she recounts. “Most people just felt like the library was being renovated.” But there were no renovations. The books sat packed up for a while, and then they disappeared. The library started to look “like a cafeteria. It was just a bunch of tables.”

Teachers were clearly upset but weren’t saying much. Neither my student nor her peers were ever given an explanation from the grownups in the building. Eventually — as kids do when they’re left to their own devices to figure life out — they started “putting two and two together.”

The students (many of whom identify as LGBTQ) had once found the school to be a safe space. They knew about Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” legislation but hadn’t known “about the book-banning laws.” Then they started noticing things that were happening once the books were gone. Gender-neutral bathrooms were renamed. Teachers had to use the names on the roster, not students’ preferred names and pronouns; they warned they might have to tell parents if they were asked to use those names and pronouns.

“My school had a big LGBTQ student population,” my student explains, and her classmates were growing “concerned about being outed.” She looks upset as she relives the memory of her last year in high school, adding that, after the books left, “We also got all these metal detectors. It was an unrelated gun incident.”

I try to nudge her toward rage — Weren’t you guys mad about the books? What did you do? — but see only pain in her face. I admire the fact that she’s choosing to stay put in her honest emotion. She’s a soft-spoken person struggling with the pain of letting go and the conundrum: What is home, now that home has become so cold?

The books eventually came back, but there were “way fewer” of them. They were also (in my words) whiter. Straighter. More aligned with the mindset of monolith and the racist, sexist, heterocentric bullshit that characterizes it.

“I felt really sad for all of the students that are there,” my student eventually says. “It’s happening in other schools, but it really changed the vibe at my school. It used to feel really fun and open and freeing and independent, and then it felt less like a college-prep art school and more like a high-security prison or a regular public high school.” The school also stopped holding Pride events. Instead, they had “a block party” that, she says, was supposed to be a “celebration of everyone’s identities.” She rolls her eyes.

Young people always see through us.

As we wind up, she tells me about the problem at New College of Florida, where “DeSantis took over the board of trustees and then replaced the president.” I hadn’t heard about it, and I’m embarrassed. “He stacked the board of trustees with conservative members. He put gender studies books in the garbage,” she explains.

“Some of us call him DeSatan,” she laughs. It’s the first time she’s done so since granting me the opportunity to speak with her about her last year in high school. Then her face sobers. She hopes to “never move back to Florida,” but she remains concerned. Home is home, after all, and this bright and compassionate young woman is neither sure what will happen to the place she came from nor sure where she’ll go.

One has to wonder: Is this what the grownups really wanted? Is this what the reworking of school libraries was for?

Sarah Trembath is an Eagles fan from the suburbs of Philadelphia who currently lives in Baltimore with her family. She holds a master’s degree in African American literature and a doctorate in Education Policy and Leadership. She is also a writer on faculty at American University. She reviews books for the Independent, has written extensively for other publications, and, in 2019, was the recipient of the American Studies Association’s Gloria Anzaldúa Award for independent scholars for her social-justice writing and teaching. Her collection of essays is currently in press at Lazuli Literary Group.