Some childhood favorites should remain in childhood.

Gifts in our family are often rectangular and a couple inches thick. Gift-guessers have it easy. The surprise isn’t what it is — a book — but which it is. This past December, I received a gently pre-read biography, The Secret Life of the Lonely Doll: The Search for Dare Wright by Jean Nathan.

Wright’s series of Lonely Doll books, published in the 1950s and ‘60s, were among my childhood favorites. The big-format picture books remained on the family shelves during our kids’ childhoods. The stories featured solemn doll Edith and her adopted family of two Steiff bears, gruff Mr. Bear and mischievous Little Bear. Wright, a fashion model and photographer, chronicled Edith’s adventures and misadventures in brief narratives illustrated by her black-and-white photo tableaus of her characters.

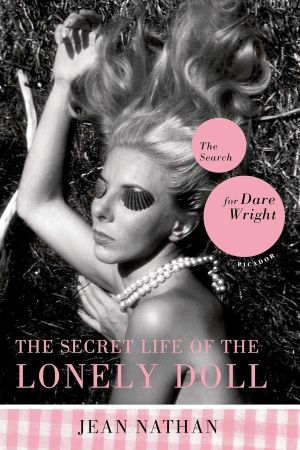

Unwrapping The Secret Life of the Lonely Doll, I discovered a startling cover: a black-and-white photograph bordered by pink-and-white gingham, exactly the cover design of the Lonely Doll books. But rather than Edith, this cover girl is blonde, glossy, glamorous Dare Wright herself. She lies like a beached mermaid on a bed of seaweed, eyes covered by fluted shells. Sleeping or drowned?

Feeling a premonitory shiver, I put the book aside, not opening it during the dark days of winter, waiting until summer. It proved chilly reading, even in the hammock.

Nathan explains the well-chosen image was staged by Dare and snapped by her mother (a portrait painter of some renown and greater vanity). Mother and daughter were obsessed by appearance and stereotypical feminine allure. Wright often photographed herself. She may have been her own model — her own living doll — but she was her mother’s puppet in a relationship as intense as lovers. Her parents divorced when Dare was very young. The girl was her mother’s chosen trophy; her father “got” her brother. The siblings only met again as adults. Their subsequent sibling relationship was also like that of lovers, to her mother’s ire.

In the biography, Nathan meticulously researched Wright’s constricted personal and creative life. The pervasive thematic undercurrent goes well beyond loneliness to abandonment, exploitation, abuse, and vulnerability. The dark side of Wright’s life is embedded in her books’ themes.

Edith’s mischief, incited by Little Bear, often teeters on the edge of transgressive, precocious behavior. Brusque, affectionate, protective Mr. Bear is a strict disciplinarian and sometime-spanker. In retrospect, I believe the mysterious under-story accounts for the pull exerted by the Lonely Doll books on at least some readers (young and not so young). Designed to be read aloud, the text is easy enough for emergent readers to take on solo. The photographs really carry the story, loaded with camouflaged subtext potent enough to draw readers back again and again over the years.

The summer I was 12, a rising seventh-grader, I went on vacation with my best friend. Aspiring authors, we staged and photographed tableaus of our dolls on the dunes of an island beach in New England. Inspiration? Dare Wright’s Holiday for Edith and the Bears, photographed on Ocracoke Island.

The summer I was 12, a rising seventh-grader, I went on vacation with my best friend. Aspiring authors, we staged and photographed tableaus of our dolls on the dunes of an island beach in New England. Inspiration? Dare Wright’s Holiday for Edith and the Bears, photographed on Ocracoke Island.

Our book was never completed, but thanks to my friend’s archive, we still have the pictures. No one got spanked, no toys were harmed. Two preteen girls played dolls on the beach. Regressing a little? Maybe. But in charge! Directing and staging a drama by exploring new (perhaps dangerous) territory. Our players were smaller and happier than Edith. And we were happy, too. Fortunate, secure kids. Co-creators controlling our subjects’ adventure.

After that summer? We put the dolls away and went on to explore the new territory of junior high and the transformative, dramatic adventure of adolescence.

Dare Wright never put Edith and the Bears away — except in a safe-deposit box. They’d become her meal ticket, her reputation, her identity. Her professional life was controlled by the doll and the bears, as well as by the loyalty of her readers and the demands of her publisher. In her personal life, her mother continued to pull the strings.

Nathan, too, read the books as a child and remained a little haunted by the Lonely Doll. As an adult, she hunted down the author, finding Wright hospitalized in a care facility for the indigent. Elderly, mute, and as unresponsive as a doll — not quite abandoned but alone. Wright’s executor bequeathed Nathan the author’s archive. With this biography, Nathan gives voice to the disturbing life of a lonely woman.

Up in our summerhouse attic, I looked without success for my Lonely Doll books. Maybe the dolls are hiding in a box or footlocker; it was too hot to keep searching.

Only one title in the series is held in the District of Columbia library system, A Gift from the Lonely Doll. I’ve reserved it, and it’s waiting for me now. It’s the one where Edith knits a scarf for Little Bear. I remember it fondly but find myself putting off going to collect it, somehow reluctant. Still, I hate to imagine Edith waiting by herself there on the hold shelf. In just a few days, she’ll be consigned back to the stacks. I must bring her home.

My best friend (yes, that same one; we are indeed BFFs) asked if she should read The Secret Life of the Lonely Doll. No, I told her. Sometimes, it’s best to let sleeping dolls lie.

Ellen Prentiss Campbell’s collection of love stories is Known By Heart. Her story collection Contents Under Pressure was nominated for the National Book Award, and her debut novel, The Bowl with Gold Seams, won the Indy Excellence Award for Historical Fiction. Her novel Frieda’s Song was a finalist for the Next Generation Indie Book Award, Historical Fiction. Her column, “Girl Writing,” appears in the Independent bi-monthly. For many years, Campbell practiced psychotherapy. She lives in Washington, DC, and is at work on another novel.