In a Baltic city full of Ukrainian flags, residents view classic Russian authors with fear and loathing.

On a main square of Lithuania’s capital, two large metal hooks remain on the wall of building number 20, Didžioji Street. Early in 2025, the city of Vilnius decided to remove the Dostoevsky plaque there — along with Russian-language plaques throughout the city.

At a Vilnius hotel with rooms named after famous authors, a new receptionist has heard that some Lithuanian and Ukrainian guests don’t want to stay in the Dostoevsky or Tolstoy room. “It evokes strong feelings,” he says. “If it were me, I’d change it.”

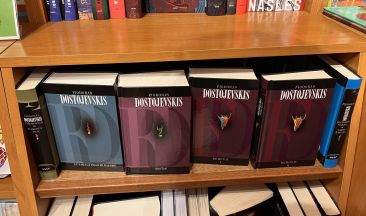

At bookstores in the city, there are works in English but no longer ones in Russian — even though a significant percentage of residents understand Russian. “We stopped selling them right when the [Ukraine] war started,” says a cashier. They did not want money flowing to Russian publishers. Another bookstore worker adds that the Dostoevsky books translated into Lithuanian sit on a low shelf and “aren’t purchased often.”

What do book lovers do when classic works suddenly represent an enemy power? Can we psychologically separate a work of art from the language and culture that birthed it? Do we even want to? Walking through this Baltic city, where yellow and blue Ukrainian flags fly everywhere, it’s clear the cognitive dissonance is too great. Shutting down anything Russian is a defense mechanism for people who are — with very good reason — afraid.

“Lithuanians can’t forgive the past and this current war. They don’t want to play Tchaikovsky. They transfer their anger to literature, the ballet, even though these things have nothing to do with it,” says a teacher of Russian literature. A native Lithuanian, she explains that she has always struggled to reconcile her love for Russian writers with her country’s history. “All my life, I never felt comfortable with it.”

She, like almost everyone else here, can name friends and relatives who suffered deportation, brutal imprisonment, or execution at the hands of the Soviets in the years after World War II. But Russian masterpieces nonetheless drew her in. “I read War and Peace at school and I found it incredible,” she admits, adding that she continued her studies despite misgivings. “I’ve always been an outsider.”

As more and more people are killed in Ukraine — and as Lithuanian civilians start learning how to shoot — the teacher feels that Russian literature is being misinterpreted and vilified. “People don’t know how to read,” she says. “Dostoevsky is a polyphonic writer,” and his characters voice conflicting viewpoints. “If you want to find XYZ in Dostoevsky, you’ll find it.”

At a Lithuanian art museum, a guide says, “We’re breaking from old writers like Dostoevsky. They were promoted a lot. We don’t know as much about Lithuanian or Ukrainian poets.” She’s happy that the school system is shifting to those writers now. During an exam, her teenage daughter “had a poem from a 24-year-old partisan who died,” a woman poet who fought for Lithuania’s freedom after World War II. Asked if a venue linked to Russian literature is worth visiting, she looks aghast. “Better visit the genocide museum.”

“If I had to speak Russian to survive, I would,” says a tour guide in the city center. But otherwise, “they can burn in hell.” She recalls what her grandmother said about her grandfather, who, in Soviet times, came back “a shell” after what the family believes was torture. Still, the guide concedes that “books are not the enemy.”

At the post office, in a theater, in a parking lot, people grimace and turn away when they hear Russian spoken. “People are angry. It’s human nature,” says the teacher. “I understand it, though I don’t think it’s correct.

“As a teacher of Russian literature, I’m sad,” she goes on. “You can’t understand society, what’s going on now, without studying its origin.” She continues to teach Russian classics — and to deal with awkward conversations. “Even if you don’t like Russian literature, you need to analyze it, not deny it.

“Dostoevsky is necessary. If you close your eyes, you’ll lose.”

Laura Sheahen is an American writer based in Tunisia. She has a master’s degree in Russian literature.